Science of reading informed strategies

If you’ve been paying attention to the education news lately, you know that the science of reading is popping up everywhere—from legislation in states across the country, to podcasts detailing the ways in which teaching reading has fallen short, to the “revelation” that we have been sitting on decades of research that guides us in understanding what works and what doesn’t.

Whether you are new to the science of reading and understanding how to implement evidence-aligned instructional strategies, or you are already weaving science of reading-based instruction into your curriculum, these 11 reading strategies will offer you ideas for your teaching or some fresh perspective on bringing evidence-aligned strategies into your district, school, or classroom. Some of these are also ideas you can offer for at-home practice.

Key findings of science of reading research

Research shows that after evidence-based instruction, the percentage of first graders below the 30th percentile can be reduced to 4-6%. In other words, with high-quality, evidence-aligned instruction delivered by a knowledgeable teacher, 95% or more of our students can learn to read (Foorman, Breier, & Fletcher, 2003; Mathes, et al., 2005; Torgesen, 2004 & 2005). There have been assumptions previously that most people could learn to read naturally, or on their own. We now know that because reading is not naturally occurring, a significant portion of the population requires explicit, systematic instruction of foundational reading skills to learn to read (Lieberman & Lieberman, 1989).

The National Panel of Reading Report in 2000 identified five components necessary for teachers to explicitly instruct on: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Although they were identified as pillars, they are not separate entities, nor should they be siloed in instruction. They are critical components in the process of reading instruction and should be integrated, not isolated.

The National Panel of Reading Report in 2000 identified five components necessary for teachers to explicitly instruct on:

- Phonemic awareness,

- Phonics

- Fluency

- Vocabulary

- Comprehension

Although they were identified as pillars, they are not separate entities, nor should they be siloed in instruction. They are critical components in the process of reading instruction and should be integrated, not isolated.

Phonemic awareness: the understanding of and ability to identify, isolate, blend, and manipulate the smallest sounds, or the phonemes, in words. This is a foundational prerequisite for reading readiness. Deficits in phonemic awareness are one of the first signs that students may have difficulty learning to read.

Phonics: instruction on the alphabetic system, or the way each sound or phoneme maps to a letter or spelling pattern. By giving children instruction in understanding of “the code,” they are able to automate the process of sound/symbol recognition—allowing them to quickly recognize words and patterns that are used to break down unfamiliar words more easily, and ultimately, to free up mental energy allowing for deeper comprehension and connection.

Fluency: requires mastery of word recognition skills for accuracy and automaticity. Fluency also entails prosody, or expression. It is important to remember that fluency is not an end but a critical gateway to comprehension. Fluent reading frees cognitive resources to process meaning, and in turn, helps with text comprehension.

Vocabulary: students with limited vocabulary will struggle with reading fluency and comprehension. For students to close the vocabulary gap, they need vocabulary instruction that both teaches the meaning of well-chosen words and shows them how to learn words on their own. In particular, a breadth and depth of vocabulary offers students added background knowledge on different topics allowing them to more easily anchor new information to knowledge they already have.

Reading comprehension: Although comprehension is the ultimate goal of reading instruction, and necessary for students to cultivate a deep love of reading, instruction on comprehension strategies that will help to form these internalized habits is important. Vocabulary and background knowledge are also key to reading comprehension. Being able to deeply understand and make connections to what’s happening in a text allows students to have “a conversation” with the author and to experience any text on a higher level.

Now that we have an understanding of the 5 components, let’s dive into the strategies that support each.

Science of reading informed strategies

Below are 13 explicit science-of-reading-informed strategies to consider in your literacy instruction toolkit. These are also ideas educators can share with parents.

Strategy #1: Phoneme isolation with objects

Being able to isolate the initial, medial, and final sounds in a word is one of the first skills we build for reading readiness. Additionally, if students have practiced at length and continue to struggle, this is a sign that there could be an obstacle.

Reading component: Phonemic awareness

Recommended age: Preschool-age kids—but can work with kids as young as 2!

Steps to implement:

- Gather a pile of small objects—ensuring that at least a few of them begin or end with the same sound. This works best with simple CVC words like “cat”, “bat”, “cup”, “cub”, etc.

- Go through and name each object, emphasizing the different sounds in each.

- You can start by asking, “Do cat and cub start with the same sound?”

- Once kids can identify this, then you can ask them to group objects by initial sound or final sound, and eventually medial sound.

Purpose

A child’s level of phonemic awareness on entering school is widely held to be the strongest single determinant of the success that she or he will experience in learning to read (Hogan, Catts, & Little, 2005).

Strategy #2: Phoneme segmenting and blending

When students are able to hear and pull apart all the sounds that make up a word, it is a very solid sign of readiness for phonics and for reading in general. This is a strategy you can turn into a game to play with children as soon as you notice they can isolate sounds.

Reading component: Phonemic awareness

Recommended age: Preschool/kindergarten

Steps to implement

- Start with simple CVC words such as “cat.”

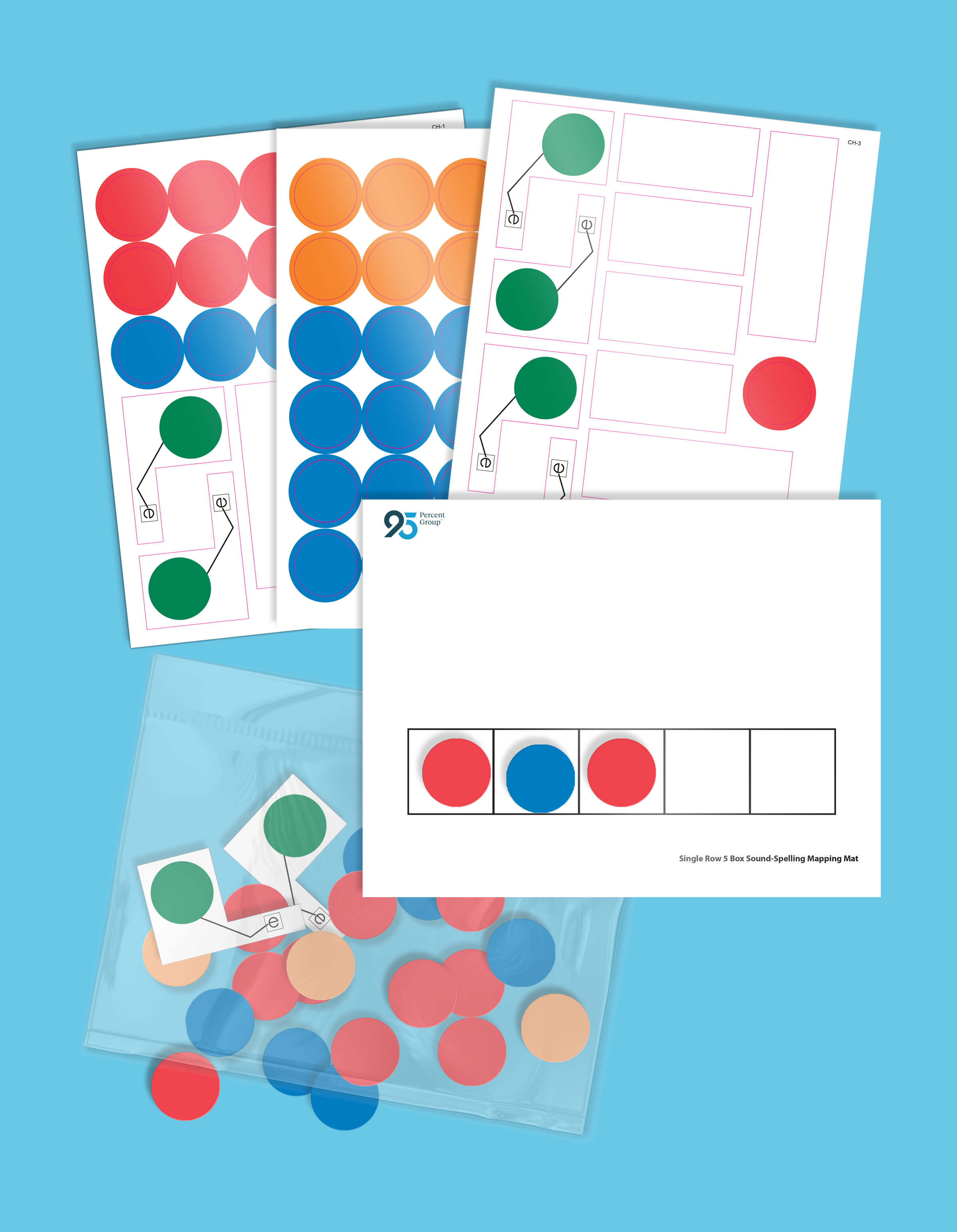

- You can use sound-spelling mapping for this to help make it more concrete. For sound-spelling mapping, students use phonics chips to represent the sounds in a word and physically move each chip into its designated box to spell a word.

- Put 3 chips underneath the boxes.

- Say the word out loud.

- Ask your students to think about what sounds they hear inside the word.

- For each sound they hear, have your students move a chip into the box in the order they hear it. (/c/-/a/-/t/)

PurposePhonemic awareness isn’t a natural skill. Many people do not attend to the sounds of phonemes as they produce or listen to speech. Instead, they process the phonemes automatically, directing their active attention to the meaning of the word as a whole.

By directly teaching how to identify phonemes inside a word from the beginning, (its parts and how they make up the whole instead of looking at the whole word first) you are offering a word attack strategy as language becomes more sophisticated.

Strategy #3: Decoding and blending using finger tapping and sound sweeping

When you recruit multiple senses to the practice of phonics, it creates a “stickiness” to the material—not only for students with reading challenges, but for all students learning to read. Using the fingers of the non-dominant hand from left to right when you say the sounds in a word, helps students to map and retain the orthographic pattern of the sounds.

Reading component: Phonics

Recommended age: Kindergarten-2nd Grade

Steps to implementing finger blending

- Present a word (e.g., snap).

- Have students hold up their non-dominant hand (non-writing hand).

- From left to right, tap out the sounds in the word: /s/ /n/ /a/ /p/ starting from the left side and tapping fingers on the thumb or on a surface while saying the sounds.

- Then say the sounds together to form the word.

Purpose

Pulling the sounds in the word apart in order to figure out what the word is helps students to understand that each phoneme maps to a letter or group of letters. This enforces the alphabetic principle—mastery of which is foundational to automaticity and fluency.

Steps to implementing sound sweeping

Sometimes, students will do OK with isolating the sounds in a word to decode. But when it comes to putting them back together to blend the sounds, they struggle. Using a finger or a pencil can help students to pull the sounds together more effectively.

This works well when practicing writing words as well.

- Say the word you want to blend and write out loud (e.g., shock).

- Have students tap out the sounds like they do for finger blending (/sh/ /o/ /k/).

- Next, have the student write the word, saying each sound as they write it.

- Then have students use their pencil to underline or sweep under the word as they elongate the sounds and blend them together: ssshhhooooccck. This helps to show the way the sounds blend together.

- Then, say the word the way it is pronounced.

- Repeat with another word.

Purpose

This multi-sensory strategy (hear it, say it, write it) that works well for all students learning to read and write. When we engage in more than one sensory experience, information is absorbed in a different and more “sticky” way.

Strategy #4: Airwriting

Airwriting, another multisensory approach to teaching phonics, is easy to do wherever you are. By using your whole arm (starting at the shoulder), your body is using muscle memory to reinforce the sound each letter or phoneme makes with the shape made with the whole arm in the air.

*This activity is especially helpful for frequently confused letters like b and d.

Reading pillar: Phonics

Recommended age: Preschool-1st Grade

Steps to implement

- Have students stand up and pretend there is a giant chalkboard or whiteboard in front of them.

- Using their writing hand, students hold their arms and wrists straight in the air.

- Have your student say the sound /m/, while forming the shape of the letter in the air with a straight arm.

- Repeat the same sound 3 times.

Purpose

While this is a method frequently used for students who have dyslexia, it is effective with all types of readers, and is a great way to get your students out of their chairs and using their whole body. When kids engage multiple senses in their learning process, information is more easily absorbed and retrieved.

Strategy #5: Readers’ theater

Readers’ Theater is a fantastic way to practice fluency and expression with repetition of text in a small group. This is an activity that can begin using pre-prepared scripts when children are first introduced to Readers’ Theater, and then can progress to students writing their own scripts—integrating reading, writing, speaking, and listening in an authentic context.

Reading component: Fluency

Recommended age: 2nd-5th Grade

Steps to implement

- Teachers can buy or print out Readers’ Theater materials based on grade or reading level.

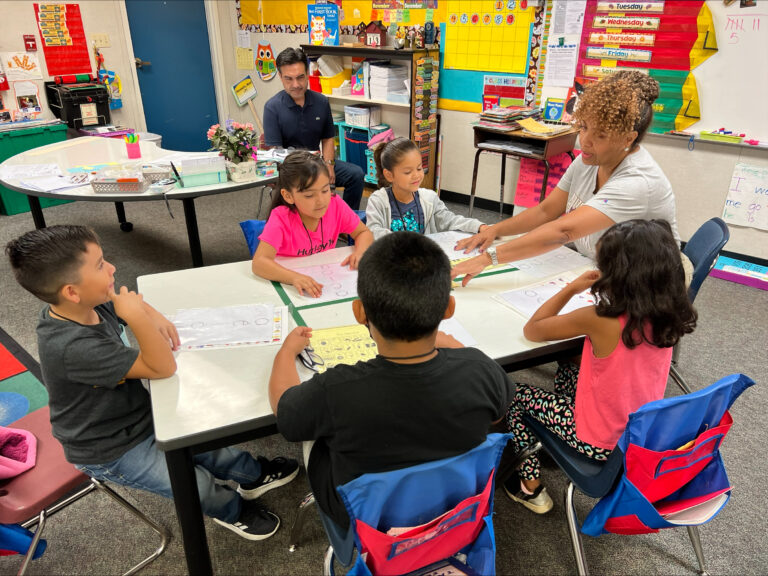

- Students work in small groups; each person has a specific role to practice.

- Students can start by highlighting their script where their own lines are in order to identify what they need to practice.

- Students can practice lines on their own first, and then together in order to prepare an informal performance.

Purpose

When children are offered an authentic opportunity for repeated reading practice, this enables them to work on fluency, expression, and prosody—all ultimately helping them towards the goal of greater comprehension and depth of understanding of character and plot.

Strategy #6: Morphology: Affixes and root word study

The study of word parts is an important part of being able to break down unfamiliar words and their meanings. This becomes especially important as students begin to encounter more academic vocabulary and sophisticated text in upper elementary and middle school.

Reading component: Vocabulary

Recommended age: 2nd-8th Grade

Steps to implement

- Using a list of Latin or Greek affixes and root words, teach students the meaning of different prefixes and suffixes while giving a variety of different examples of how they are commonly used.

- Additionally, show students how they can use their knowledge of affixes and root words to break apart unfamiliar words and figure out parts of words in order to help with difficult reading tasks.

Purpose

When students have strong morphological skills, they can approach an unfamiliar, multisyllabic word and break it into parts in order to predict the meaning. This is a foundational skill that offers an advantage in all areas of literacy: decoding, spelling, comprehension, and oral language.

Strategy #7: Academic vocabulary squares

When students have a deep understanding of vocabulary, their content knowledge develops roots. By guiding them to look at multiple angles of a word, students can more easily internalize word meanings, allowing for a greater chance of retrieval and subsequent anchoring of new knowledge in the future.

Reading component: Vocabulary

Recommended age: 3rd-12th Grade

Steps to implement

- Print out a template for vocabulary squares or have students create a box with 4 boxes inside in their notes.

- Students write the word at the top or in the middle of the 4 squares.

- For each of the 4 boxes, give students a different way of understanding each word. (e.g., definition in the first box, synonyms in the second box, antonyms in the third box, and a sketch or drawing that they associate with the meaning in the last box. These can be customized however you need, depending on the grade).

Purpose

By breaking down all the aspects of a new word and looking at the definition but also synonyms or associated words, it’s more likely that students will be able to anchor the new information to something they already know. This helps to deepen understanding and aids in future knowledge retrieval. This is often referred to as Meaningful Learning.

Strategy #8: Double-sided note-taking

When reading to learn, it’s helpful for students to interact with the text in a way that will help them to define unfamiliar concepts as well as to ask questions about those they are trying to connect to. By putting fragments of the text (quotes) or unfamiliar words or questions they have on one side of the page and then writing definitions, answers, explanations or interpretations on the other side, they can help integrate all of the knowledge in one place.

Reading component: Comprehension

Recommended Age: 2nd-12th Grade

Steps to implement

- Have students draw a vertical line down the middle of their page.

- On the left hand side at the top, they can write Concept/Question/Quote.

- On the right hand side at the top, they can write definitions, answers, interpretations, etc.

- When students come across an idea, an unfamiliar word, a quote or detail that’s important to the main idea or purpose for reading, they can record this on the left side of their notes and then add their own thoughts on the right side. This can serve as a great resource to go back to when students need ideas for a response to reading.

Purpose

By using this method for note taking, students will have a framework into which they can pour new vocabulary knowledge, connections they make about characters, setting, the main point and details, or ask questions that they can come back to as they read and learn more. All of these actions taken while reading help students to retain and weave information into their already existing schema.

Strategy #9: Writing about reading

Author Joan Didion once said, “I write to know what I think.”

Writing about reading is an effective way to aid students in thinking more deeply about what they are reading. When reading is required, it’s often easy to skim for information, especially if there are comprehension questions to answer from the text. When we ask students to write about their reading, we are asking them to dig a little deeper than just the plot; we want to know what they think about what they’ve read. And often we don’t know this until we can put words on the page.

Reading component: Comprehension

Recommended Age: 2nd-12th Grade and beyond

Steps to implement

- Let students know before their reading assignment that they are going to be writing a response about what they’ve read. This can be intimidating for those students who aren’t used to thinking about what they themselves think about their reading. Offering some prompts can be helpful when getting started—especially for younger readers. Here are some suggestions:

- Offer prompts or sentence starters like, “I wonder if…” or “This character reminds me of…” or “When _________ (Character) did/said/thought __________, it made me think that…” Alternatively, you can choose the quote, phrase, word, and have all students write on the same idea until they are more confident choosing something on their own.

- Set a timer. Encourage students to write for the whole time until they hear the timer go off.

If students say they don’t know how to start or are stuck, have them write the word stuck on the page over and over until something else comes out. Sometimes, thought follows action.

Purpose

Writing about reading offers students a way into critical thinking when it can feel intimidating to offer their own thoughts. This is a strategy that will help readers that are just beginning all the way up through college. It’s an easy activity to scaffold and release ownership of, once students are comfortable and confident with their own ability to identify what to explore in their response.

Strategy #10: Book groups

Allowing students to have ownership of what they choose to read can go a long way—especially with students who may be reluctant readers. By grouping students together to read and discuss a book, you are offering a format that’s out of the ordinary when compared to whole class work. It allows for a smaller (sometimes less intimidating), more targeted experience where all members of the group can participate and feel heard.

Reading component: Comprehension

Recommended age: 1st-12th Grade

Steps to implement

- Before having students choose books, spend some time in whole-class or small-group conversation about what makes book groups successful. You could even draw up an agreement and have all students sign the agreement, or you can have groups do this on their own once they are formed.

- Depending on the age/grade level/group dynamics of students, you can assign books, or you can offer choices and let students “group themselves.”

- To do this, offer a handful of different books (it works well to base book choices on a general theme or, historical period or another topic you know you (or other teachers) are exploring during the time they will be reading.

- Before students are in groups, teachers should define rules and roles each person will have in their group. Some rule suggestions might be: no reading ahead, a decision on what will happen if a group member can’t complete the reading etc., how will we ensure everyone is participating in discussions? etc.

- Students should complete reading at home or during a designated time in class.

- Once in groups, the teacher can provide discussion questions or students can generate ideas on their own.

- It’s a great idea to end book group discussions with some writing about reading (see previous strategy) and with assurance that each student knows the assignment for the next meeting.

PurposeAround 1st or 2nd grade and forward, most children become increasingly interested in social interactions. Book groups are a great way to infuse a social element into reading. By grouping students together and creating a community around the book they are reading, it offers a smaller, more informal way for students to ask questions, explore their ideas, and to get help should they need it. While this format is not designed to take the place of explicit, systematic instruction in foundational reading skills, this is an alternative format to teacher-led reading groups.

Strategy #11: Making connections

Students make connections between what they read and what they already know—as well as to their own life experiences or to ideas or characters they have read about previously. It helps to anchor new information to an existing, familiar knowledge schema. When teaching students how to make connections to something they’ve read, remind them that a connect can be:

- A text-to-text connection: it reminds them of something they read in another text

- A text-to-world connection: a connection between something they read and something in the world around them—including current and historical events

- A text-to-self connection: a connection between something they read and something they themself have experienced or a feeling they have inside.

Steps to implement:

- Making connections can be done in discussion or in note taking (sometimes double sided note taking works for this!)

- Students can use sticky notes to write down a connection and stick it in their notes or right in a text

- Have students choose a few connections they made while reading and discuss in pairs or small groups

- Write the 3 types of texts on chart paper or a white board and have students can add their sticky notes under the type of connection they believe they made

Purpose

When children can make connections to what they are reading they are more likely to see themselves in the story or to experience something through the eyes of a character. Ultimately, reading can play a big role in learning about perspective-taking and making connections is one way to help students think about their experiences in a more universal way.

Reading component: Comprehension

Recommended age: 1st-12th Grade

Strategy #12: Synthesizing

Synthesizing means a reader develops their own idea about the message learned by determining which information is important and combining the key ideas identified. Said another way, it’s what emerges, fully baked, from all of the ingredients in the text. Honing this skill allows readers to have a deep understanding of what they’ve read and an integration of this knowledge with their own experiences. It’s what we take away from reading a text and can apply to our own lives or situations.

This is another strategy for which writing about what they’ve read can help a reader to know what they have gotten out of reading a text. This can also sometimes be a combination of summarizing, reflection, and making connections.

Steps to implementing:

- Upon finishing a text or a chapter, have students spend some time writing about their reflections. Sometime guiding questions help here:

○ What are the main things that happened in the story? List them.

○ Use the list of events to write a sentence about what you think the meaning or main message in the story is.

○ Find details from the story that support your idea.

○ Make a connection: Write a few sentences about how this makes you feel or maybe an experience you have had that’s similar.

Purpose

Synthesizing goes beyond summarizing to find a deeper meaning in what the reader understands. It helps the reader to have their own personal interpretation of what the theme, or message, of the story.

Reading component: Comprehension

Recommended age: 4th-12th Grade

Strategy #13: Strategic re-reading

When a reader gets to the end of a text, often there will be parts that weren’t fully absorbed. This is especially true when reading nonfiction or informational text. Attending and attuning completely to everything in an informational text is difficult—especially for readers that are still learning how to discern and move between comprehension processes. This makes strategically rereading different parts of a text a key strategy for ensuring full comprehension.

Steps for implementing:

- Start by asking students to notice parts (paragraphs, chapters, or sections) of the text that seemed confusing or that didn’t fit with other parts they read.

- These are places they can go back and reread to figure out what they need to know from that section.

- It’s helpful to consciously combine other strategies here to help students draw out information. Have them highlight, underline or circle ideas or vocabulary words that help them have a deeper understanding of what the text is saying.

- This will help the reader to really focus on anything they may have missed.

Purpose

Rereading can also be considered part of comprehension monitoring or checking for understanding. By practicing noticing places you didn’t fully understand what you read, you are giving yourself the chance to fill those gaps by going back to reread parts you found confusing, or that don’t fit the context of what you read. This skill requires higher order thinking and be able to know when you don’t fully get something.

Reading component: Comprehension

Recommended age: 4th-12th Grade

Tips for parents and teachers

When looking to implement one or more of these research-based reading strategies at home or in the classroom, there are a few things that might help you:

- Try one strategy at a time. If your students or child don’t get it at first, keep trying. Sometimes it takes a few times to get it down.

- When you are asking children (especially children who are struggling with phonemic awareness or phonics) to say a sound and write a sound at the same time, it might be challenging. Be patient. Keep modeling this skill. The repetition of sounds while writing the letter is an extremely effective multisensory approach to teaching phonics.

- If you have younger children (2-3), play these games when you have a few minutes in the car, or in the waiting room somewhere. Young children are really drawn to language and love to play games. Playing a sound game (I’m thinking of something in the room that starts with /b/) is easy, free and fun! It’s a great way to get phonemic awareness started.

- For older kids, you can play games where you first say the sounds in a word (/c/-/a/-/t/) and have them put the sounds together and say the whole word, “cat.” Then you can ask them to pull words apart into the sounds (what are the sounds in the word “cat”?).

- Any time you can sneak these little skills in—even for a few minutes at a time, you are offering your children or students another building block in their reading and language readiness.

Using science of reading strategies to support children with reading disabilities

Students that have a reading disability like dyslexia, for example, truly benefit from a structured literacy approach and research-based reading strategies. Any strategy that engages multiple senses such as seeing a sound, saying a sound, and writing a sound goes much further towards retention and retrieval of that sound or skill.

The final word

When it comes to science-of-reading-informed strategies, it’s helpful for literacy instructors to have many different tools in their instructional toolkits to use with students. 95 Percent Group’s One 95 Literacy Ecosystem™ addresses literacy instruction across Tier 1, Tier 2 and Tier 3—offering districts and schools a streamlined and systematic approach to reading instruction for all students—including those who require intervention as well as those who need enrichment.

References

- Foorman, B. R., Breier, J. I., & Fletcher, J. M. (2003). Interventions aimed at improving reading success: an evidence-based approach. Developmental neuropsychology, 24(2-3), 613–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/87565641.2003.9651913

- Liberman, I. Y., Shankweiler, D., & Liberman, A. M. (n.d.). The alphabetic principle and learning to read. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED427291

- Mathes, P. G., Denton, C. A., Fletcher, J. M., Anthony, J. L., Francis, D. J., & Schatschneider, C. (2005). The effects of theoretically different instruction and student characteristics on the skills of struggling readers. Reading Research Quarterly, 40(2), 148-182.

- Torgesen, J. K. (2004). Lessons Learned from Research on Interventions for Students Who Have Difficulty Learning to Read. In P. McCardle & V. Chhabra (Eds.), The voice of evidence in reading research (pp. 355–382). Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co..

- Vaughn S, Fletcher J. Explicit Instruction as the Essential Tool for Executing the Science of Reading. Read Leag J. 2021 May-Jun;2(2):4-11. PMID: 35419568; PMCID: PMC9004595.

- Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, DHHS. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read: Reports of the Subgroups (00-4754). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Hogan, T. P., Catts, H. W., & Little, T. D. (2005). The relationship between phonological awareness and reading: implications for the assessment of phonological awareness. Language, speech, and hearing services in schools, 36(4), 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2005/029)

- National Center on Improving Literacy. (2023). The Educator’s science of reading toolbox: How to build fluency with text in your classroom. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, Office of Special Education Programs, National Center on Improving Literacy. Retrieved from http://improvingliteracy.org

- Adams, M.J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Ball, Eileen Wynne, and Benita A. Blachman. “Phoneme Segmentation Training: Effect on Reading Readiness.” Annals of Dyslexia 38, no. 1 (January 1, 1988): 208–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02648257.

- Reading Rockets. “Elkonin Boxes | Reading Rockets,” n.d. https://www.readingrockets.org/classroom/classroom-strategies/elkonin-boxes.

- Reading Rockets. “Phonemic Awareness in Young Children | Reading Rockets,” n.d. https://www.readingrockets.org/topics/early-literacy-development/articles/phonemic-awareness-young-children.

- Reading Rockets. “Phonics Instruction: The Value of a Multi-Sensory Approach|Reading Rockets,” n.d.

- Element. “Multi-Sensory Learning: Types of Instruction and Materials.” IMSE – Journal, September 20, 2022. https://journal.imse.com/multi-sensory-learning-types-of-instruction-and-materials/.

- Reading Rockets. “Reader’s Theater | Reading Rockets,” n.d. https://www.readingrockets.org/classroom/classroom-strategies/readers-theater.

- Reading Rockets. “Fluency: In Practice | Reading Rockets,” n.d. https://www.readingrockets.org/reading-101/reading-101-learning-modules/course-modules/fluency/practice.

- University of Michigan. “Morphological Awareness.” Dyslexia Help. Accessed January 18, 2024. https://dyslexiahelp.umich.edu/professionals/dyslexia-school/morphological-awareness.

- Bryce, T. & Blown, E.. (2023). Ausubel’s meaningful learning re-visited. Current Psychology. 1-20. 10.1007/s12144-023-04440-4.

- Element. “Multi-Sensory Learning: Types of Instruction and Materials.” IMSE – Journal, September 20, 2022. https://journal.imse.com/multi-sensory-learning-types-of-instruction-and-materials/.