Phonemic awareness lesson plans

Phonemic awareness lesson plans for every learner

Phonemic awareness means having the ability to understand, identify and manipulate phonemes, the smallest units of sound inside words. This critical skill has been called out as one of the most important foundational literacy acquisition skills, and one of the earliest indicators of whether a child will encounter difficulty with reading.

Structured, explicit phonemic awareness instruction is at the heart of reading readiness for children in kindergarten and first grade. Having the appropriate phonemic awareness lessons in your toolbox will give you a running start on ensuring your students receive the best possible beginning to their reading journey.

Phonemic awareness lessons can cover many different skills—each builds on the one before, offering students the next step as they are moving forward. Some of these beginning skills like phoneme isolation, phoneme segmentation, blending and substitution can be assessed beforehand. As the teacher, this offers you context about what your students already know and where they need to begin along the phonemic awareness continuum.

Exploring the spectrum of phonemic awareness

There are quite a few stops along the way when teaching phonemic awareness lessons along the continuum. Assessing your students helps you understand the first instructional steps and how to meet students right where they are. While there are many different screeners, the 95 Phonemic Awareness Screener for Intervention™ is an excellent tool for this purpose. Not only does it pinpoint the skills your students still need to master, but it also maps directly to the needed skill lessons in the Phonemic Awareness Suite™.

Let’s dive into phonemic awareness skills.

Phoneme Isolation

Phoneme isolation, or the ability to separate the beginning, medial, or final sound(s) within a word, is most often the easiest skill for children to start with. This may look like students being able to hear and identify the /b/, the /a/, or the /t/ in the word “bat.” Most often, the easiest sound for students to start with is the sound at the beginning of the word, or the initial sound. The next step is the final sound, and then the medial sound–or the sound(s) in the middle of the word— which is usually the last step.

Although phonemic awareness is only about the spoken sounds in language, sometimes it’s helpful to associate the sounds with a concrete object. Small figurines or toys work well for this type of activity.

Sound game:

- Gather several different small objects, ensuring that at least a few of them have the same beginning, final, or medial sound (depending on what you are working on).

- Name each object for the student, clearly saying the name and pointing to the object. You may want to emphasize the phoneme that you are isolating for the game, i.e., “This is a cat, cat begins with /k/.”

- Ask the student to find all the objects that begin with /k/ (for example).

- You can play this game several times, changing the phoneme position that you are isolating and adding or taking away different objects as appropriate.

Phoneme segmentation and blending

The evidence is clear that teaching phoneme segmentation and blending is key. When you decode a word (sound it out), you have to blend the sounds together. When you encode a word (write it), you have to segment the sounds.

Phoneme segmentation

Phoneme segmentation is the ability to break words down into individual sounds or phonemes. For example, the word “cat” can be broken down into its individual phonemes: /k/ /a/ /t/. Segmenting phonemes is a helpful step towards fluency in reading and writing development because it helps in developing the understanding of sounds in spoken and written language. Phoneme segmentation is a little more challenging than phoneme isolation, and explicit instruction helps students understand how to listen to a whole word and then deconstruct the word by identifying each sound in the order in which it’s heard.

Finger tapping:

Combining explicit instruction with a multi-sensory approach, such as finger tapping, will support learners in identifying the individual sounds they hear within each word. For instance, cat can be tapped out using the pointer finger of the right hand against the thumb for /k/, then the middle finger against the thumb for /a/, and the ring finger against the thumb for /t/.

Sound Mapping

Mapping sounds using manipulatives is another way to use multiple senses to help visualize the different phonemes within a word. Using tokens or chips (one for each sound in the word) and then pulling them down from left to right or moving them from one place to another as you say each sound in the word, helps students to feel or understand that the sounds move from left to right in order.

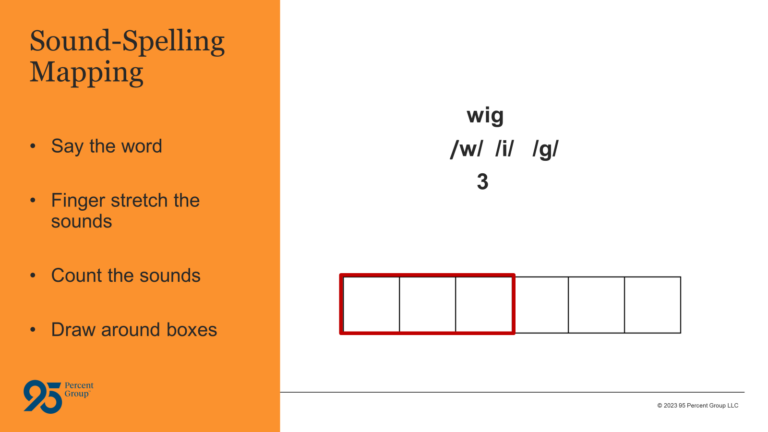

Incorporating visual aids will further support the development and understanding of phoneme segmentation. 95 Percent Group utilizes a “Sound-Spelling Mapping Routine,” either with or without chips, to support phoneme awareness and connecting phonemes to graphemes.

For example, for the word “wig,” students would do the following:

- Say the word

- Finger stretch (or tap) the sounds

- Count the sounds

- Draw around the boxes

- Pull down one sound at a time

- Write the letters below each box

- Say the word

The use of manipulatives or movement engages the students further by making the lesson more interactive.

Phoneme Blending

Phoneme blending, or the ability to build words from individual sounds or phonemes, is a step towards understanding that whole words are made of sounds.

Blending Activity (using fingers in Kindergarten and beyond)

- Teacher: say “_________.” Students echo.

- Teacher: Now, say the word slowly, stretching out one finger for each sound. Students segment and extend a finger from their fist for each sound (moving left to right, starting with the thumb). Right-handers use their writing hand palm down; left-handers turn their writing hand palm up so the hand unfolds in a left-to-right sequence.

- Once the correct sounds are segmented, students repeat the sequence of sounds on the fingers.

- Now blend the sounds and say the word. Students say the word.

Phoneme manipulation: Addition, deletion, and substitution

As the name implies, phoneme manipulation is the ability to delete or substitute a given phoneme in any position within a word. For example, remove the /i/ in the word slip and replace it with /a/. Now, you have the word slap.

While there is no evidence that mastery of phoneme manipulation is required for reading fluency, some experts suggest it is helpful for some students. Also, practicing manipulation of sounds with letters can be helpful to reading and spelling.

Addition: adding a phoneme to an existing word. If you start with the word top, and you add /s/, now you have stop. As students become more comfortable with this, they can add multiple phonemes simultaneously.

Deletion: the opposition of addition. Instead of adding a phoneme, you take a phoneme away. So if you start with the word glove and you take away /g/, now you have the word love.

Substitution: this is a bit like combining both addition and deletion. You first take away a phoneme and then add another—creating an entirely different word. If you start with the word cape, and delete the /k/ (leaving ape), and then you add /sh/, you end up with a completely new word: shape.

Check out our post on the blog for specific lesson plans or activities.

What to include in your phonemic awareness lesson plans

When it comes to phonemic awareness lesson plans, structure and explicit instruction are the most important factors. For all students learning literacy skills, employing direct instruction and offering an “I do, We do, You do” approach helps students to:

- See and hear what they need to do

- Practice the skill with a teacher for immediate feedback and redirection if necessary

- Practice independently to build confidence and ownership of each skill

When looking for lesson plans to use in your classroom, you should look for the following components:

- Lessons that are aligned with evidence. Any instruction you bring into your classroom should be aligned with evidence—meaning it’s supported by the body of evidence we call the science of reading.

- Lessons that are scripted. While there are some teachers who don’t like to be required to use scripted lessons, the amount of work expected of teachers means that having a scripted literacy curriculum allows them to establish routines and systems quickly, and supports teachers in learning the instructional dialogue of the lesson. Scripted phonemic awareness lessons help both students and teachers know what to expect each day and offers a common language that removes the cognitive load of finding and planning lessons and activities.

- Lessons that are structured and sequential and allow for modeling, guided practice, and independent practice

Teaching phonemic awareness lessons

Understanding the importance of teaching phonemic awareness is the first step. But when delivering the instruction, there are some strategies that will go a long way in maximizing your time and efforts.

- Primary focus should be on teaching students what they hear with each sound and how it should feel in their mouth. There are so many phonemes in the English language that it can feel confusing for students to be able to articulate them all in the beginning. Teaching what students should hear with each sound and how it feels in their mouth and throat when a phoneme is “voiced” or “unvoiced,” helps them understand the articulation and auditory qualities of the phoneme. Additionally, teachers can first offer a photo to show how the mouth forms each phoneme, and then a mirror so students can see what shape their mouth makes when they say /p/ or /b/ compared to /m/ or /n/.

- Connect phonemes to letters (graphophonemic connections) to benefit students when learning to read and write. Phonemic awareness instruction should always begin with just the sounds in order to help children focus on the phoneme sequences in spoken words. Typically, linking letter knowledge and phonemes to read and spell words can begin soon thereafter, depending on the students’ proficiency with phonemes; however, phonemic awareness skills should continue to be taught in K-1 (and for older students as indicated) as a distinct strand of the lesson that parallels phonics instruction. When phonemic awareness instruction is connected to the representative letters or graphemes, it helps children with orthographic mapping and makes it easier to retain and recognize words when they see them again.

- Make it multisensory. Research on working memory and cognition shows us that there are benefits of multisensory experiences when teaching different literacy skills. When students simultaneously incorporate more than one sense (i.e., writing with a pencil or air writing with their whole arm while saying the sound or phoneme, it activates multiple parts of the brain (whole brain learning) than when just saying a sound or just writing the representative letter(s).

- I do, We do, You do model. When you offer a gradual release instruction model, students have the opportunity to see a skill first modeled for them explicitly, then to practice with the instructor, receiving immediate feedback and/or reteaching if needed, and last, the opportunity to practice on their own—increasing confidence, independence and student ownership of their learning. The repeated practice of a skill also increases the chance of retention.

The final word

Phonemic awareness is a subcategory of phonological awareness. While these two terms are often confused with each other, they are part of the same learning process and continuum. Direct, structured, and sequential phonemic awareness lessons are critical to a child’s eventual reading success.

95 Percent Group recently launched their 95 Phonemic Awareness Suite™ — a new, comprehensive phonemic awareness solution that includes Tier 1 instruction, assessment, differentiated Tier 2 instruction, and professional learning—all aligned to provide a consistent instructional dialogue for teachers and students. Aligned with the latest research on phonemic awareness, it’s everything needed to build critical foundational skills and set students up for reading success!

95 Phonemic Awareness Suite components include:

- Tier 1: 95 Pocket Phonemic Awareness™, 50 weeks of lessons, each 10 minutes per day (K-1)

- Assessment: 95 Phonemic Awareness Screener for Intervention™

- Tier 2: 95 Phonemic Awareness Intervention Resource™, lessons cover alphabetic and phonemic awareness, with Kid Lips instruction built-in

- Professional learning for teachers and reading specialists

Sources

- Ashby, J., McBride, M., Naftel, S., O’Brien, E., Paulson, L. H., Kilpatrick, D. A, & Moats, L. C. (2023). Teaching Phoneme Awareness in 2023: A Guide for Educators.

- Ashby, J., McBride, M., Naftel, S., O’Brien, E., Paulson, L. H., Kilpatrick, D. A, & Moats, L. C. (2023). Teaching Phoneme Awareness in 2023: A Guide for Educators.

- Davidson, Marcia, USAID, and Global Education Summit. “Scripted Reading Lessons and Evidence for Their Efficacy.” United States Agency for International Development, 2015. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://2012-2017.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1865/Davidson.pdf.

- National Reading Panel (U.S.) & National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U.S.). (2000)

- Castiglioni-Spalten, M. & Ehri L.C., (2003). Phonemic Awareness Instruction: Contribution of Articulatory Segmentation to Novice Beginners’ Reading and Spelling. Scientific Studies of Reading, 7(1), p. 25.

- Farrell, Mary L., White, Nancy Cushen; Multisensory Teaching of Basic Language Skills, Ch. 2, p.48

- Teaching to the whole brain. (2021, June 2). ASCD. https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/teaching-to-the-whole-brain

- The Reading League. (2022, June). https://www.thereadingleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/The-Reading-League-Curriculum-Evaluation-Guidelines-2022.pdf. Retrieved January 31, 2024, https://www.thereadingleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/The-Reading-League-Curriculum-Evaluation-Guidelines-2022.pdf