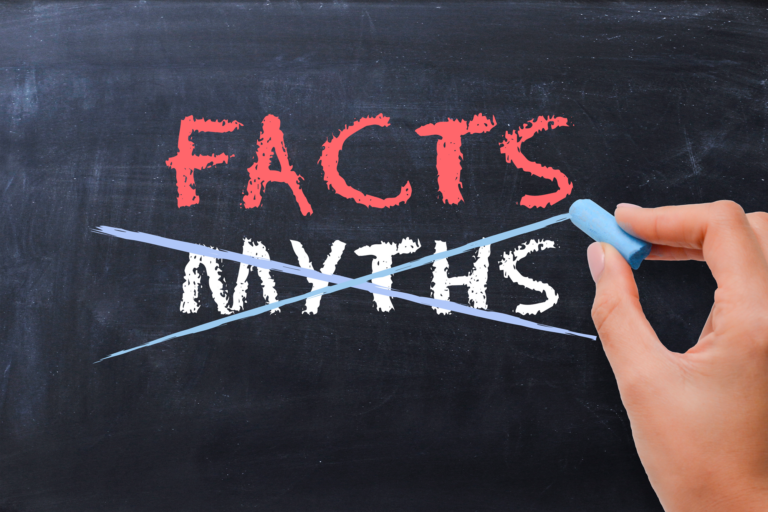

Ten myths & misconceptions in literacy today

In the latest article in her hot topics series, Laura Stewart, Chief Academic Officer, debunks the top 10 myths and misconceptions in literacy today, their origins and explains why they are problematic and what the latest and greatest thinking on them is. She also offers top sources for supporting their abandonment.

Electric typewriter. Mainframe computer. Overhead projector. Mimeograph. When I went through my teacher preparation program, they were “high tech.” Now, my laptop is more powerful than a mainframe computer; my phone is even more powerful than my laptop. And most of you likely don’t know what a “mimeograph” was. While we have advanced edtech over the years, some instructional practices are stuck in a time warp.

Reporter Emily Hanford’s Sold a Story podcast sheds light on how some reading instructional practices have endured despite a preponderance of evidence dispelling their effectiveness. And like the overhead projector, it’s time to put those practices in a file labeled “Myths & Misconceptions.” Some have always been mythical; others (misconceptions) were accepted at one time but are now disproven.

Here’s a look at some of the top “Myths & Misconceptions,” their origins, why they are problematic, current thinking, and sources supporting their abandonment.

#1: Learning to read is like learning to speak.

Children learn to speak quite naturally through hearing models, immersion in language, and lots of exploration. Early voices in this idea promoted that learning anything is a “construction” of meaning, and that reading could be constructed as well. Speech has been with us for a long time and is part of the human condition. A written code is a relatively recent invention and not universal in all spoken languages, so reading and writing are not hard-wired, like speech, into our neural architecture.

Read more: Speaking is Natural; Reading and Writing are Not by Louisa Moats and Carol Tolman

#2: Explicit instruction is only necessary for struggling readers.

The belief was that most children acquire literacy naturally so it was a waste of time for children to have explicit instruction in reading skills, except for those requiring intervention. Reading is an “unnatural act,” so instruction really counts. A very small percentage of children can learn to read easily but we don’t know who they are when they come to school.

Watch: Explicit Instruction (videos) by Anita Archer

#3: Foundational Skill instruction, particularly phonics, is “skill and drill” that will “kill” students’ motivation to read

Many of the original voices in the whole language movement diminished the importance of learning the alphabetic code.Understanding how the code works is fundamental to reading and writing in an alphabetic language. Phonics instruction is far from “dull and dreary.” Children love to learn about words and their hidden properties and patterns.

Read more: How Children Learn to Read : Toward Evidence-Aligned Lesson Planning by Louisa Moats

#4: Decodable Text is also “skill and drill” and will “kill” a love of reading

Students are motivated by reading real, authentic literature. Decodable text with repeated phonetic patterns were considered meaningless, without regard for their intended purpose of securing phonetic patterns in the early stages of reading. Decodable text is a temporary scaffold in the beginning stages of reading, allowing students to apply and secure the phonetic patterns they are learning. Young students are also experiencing authentic text as read-alouds, shared reading, and lap reading.

Watch: Decodable Texts Matter video by Marnie Ginsberg (Reading Simplified)

#5: All children learn to read differently

This is an appealing idea because all children are unique. If we believe this to be true of reading, we face a plethora of teaching choices that are perceived to all be equally effective, depending on the child. Neuroscientific studies show the brain architecture that must be created for reading is similar in all of us. This body of research paved the way for understanding instructional principles that are most effective for early readers.

Watch: Stanislas Dehaene, cognitive scientist, How the Brain Learns to Read video games

#6: English is odd. There isn’t enough regularity in the language to be able to teach replicable patterns or the underpinnings of meaning.

English has a semi-transparent orthography and a relatively complex written code. Many proponents used this reasoning to support memorizing “sight words” and utilizing multiple cues for word recognition. With instruction in the multiple layers of the English language, we can unlock the patterns of the majority of words.

Read more: How Spelling Supports Reading and Why it Is More Regular and Predictable Than You May Think by Louisa Moats

#7: Readers use multiple cues when figuring out print.

This disproven theory purports that readers utilize semantic cues (pictures), syntactic cues (context), and visual cues (within-word cues) to read and comprehend. Reading words accurately and fluently matters. Context and illustrations (when present) are back-up systems to confirm meaning.

Listen: Sold a Story Podcast, Episode 2

#8: When readers struggle with comprehension, “strategy” instruction is critical.

The thinking was that comprehension was primarily the deployment of strategies (“Main Idea,” “Cause and Effect,” etc.). These “strategies” were tasks rather than actions for navigating the meaning of texts. When students struggled, it was reasoned they needed to learn how to use these strategies.

Reading comprehension is complex; in addition to decoding skills, comprehension depends on vocabulary, syntactic knowledge, background knowledge, and the use of selected, applicable, high-impact strategies.

Read more: Improving Reading Comprehension in Kindergarten Through Third Grade; Institute for Educational Sciences

#9: We don’t know much about how reading develops and how to best teach reading; there will always be differences of opinion

Research referred to as the Science of Reading, available for over four decades, is multi-disciplinary, international, and widely accessible. While science is far from static and we don’t have rigorous scientific studies providing direction for every step of reading instruction, we know a lot and will continue to learn more as this field grows more integrated and unified.

Read more: Ending the Reading Wars: Reading Acquisition From Novice to Expert

#10: Struggling young readers just need more time

The “wait and see” approach is based on the fallacy that reading is naturally occurring and instruction doesn’t play a central role. While children develop at different rates, we know reading progresses relatively predictably; also, we have universal screeners and diagnostic assessments to identify at-risk students.

Read more: Evidence Based Assessments in the Science of Reading by LD@school

Just like the “high tech” equipment I used in my classroom decades ago, what we know about effective reading instructional practices has evolved. My hope is that by shining a light on our previously held “Myths & Misconceptions” we can unite in a vision for a future where every child has access to high quality instruction to learn to read.

Learn More

To read more by Laura Stewart, visit her most recent article in her ongoing Hot Topics in Literacy Series: Students in 4th and 5th Grades Still Need Reading Instruction? At 95 Percent Group, we are dedicated to producing evidence-aligned resources, by educators and for educators, that link research to practice. If you’d like to learn more about what we offer, please get in touch.

About Laura Stewart

Laura Stewart, Chief Academic Officer, is a nationally recognized Science of Reading and Structured Literacy advocate and expert who serves as the company’s spokesperson and continues to build its thought leadership position in the literacy market. Stewart has dedicated her career to improving literacy achievement at leading education companies including The Reading League, Highlights Education Group, and Rowland Reading Foundation.