You can use sound/spelling walls in any classroom. Instructional know-how is critical.

During a four-day professional development session at an elementary school, Dr. Mary Dahlgren and I were given a tour of the school’s newly remodeled early childhood wing. The rooms were spacious, with big windows to flood each classroom with natural light and an abundance of wall space to display masterpieces created by each young learner. At one end of the room was a word wall, which was and continues to be a standard resource in many EC classrooms.

Like many similar classrooms, the word wall was organized around the letters of the alphabet and yet tasked with representing the 44 English phonemes. A Cheerios boxtop had been placed under the letter “c.” Another of Lucky Charms, with the /ch/ underlined, was also placed underneath its companion Cheerios cereal partner. Under the letter “s” were words like sun, seal, and other words that made perfect sense. Unfortunately, we also saw the words shamrock and ship.

Over the years, Dr. Louisa Moats, our mentor and teacher, had discussed this dilemma with us and other reading instructors and colleagues. Learning to read and write is not a visual but a linguistic skill. Obviously, we need our vision to see what we are reading or writing, but when it comes to linguistic skills, students need to be explicitly taught the connection between phonemes and graphemes, moving to a speech-to-print approach. Teaching the articulatory features of each phoneme can further help the students develop stronger phonemic awareness skills.

We took what we had learned from our experiences with Dr. Moats, the work of Dr. Linnea Ehri and her colleagues, and the fact that we needed a better way to organize our sound/spelling system, and we wrote the Kid Lips curriculum. We also wanted to help define phonological spelling errors and support teachers with the corrective feedback they could provide students. As half of the writing team and as an English learner, I remember telling Mary that sound/spelling walls can also provide the perfect platform to teach the phonetic structures of English phonemes and help students make cross-linguistic connections between the phonological systems of English, and in our case, Spanish. We realize there are hundreds of languages spoken across the country, but the most spoken, other than English, is Spanish, with over 3.5 million ELs identifying Spanish as their home language. The cross-linguistic challenges our native Spanish-speaking students experience can be applied to other languages.

The purpose behind the creation of Kid Lips and sound/spelling walls has been to:

- Teach students the relationship between the phonemes and graphemes that represent them;

- Describe the articulatory features of phonemes that can further solidify the phonemic awareness skills they possess;

- Give teachers the linguistic tools to explain common phonological spelling errors;

- Provide students with the cues, both keywords and mouth pictures, to help them with spelling and articulation; and

- Provide a resource that helps teachers explain to English learners and students with dialectal variations the articulatory features of how English phonemes are produced—not to correct articulation but to support and better explain it when those features or gestures do not exist in the student’s home language.

In a recent podcast, we were relieved to hear one of the guest speakers state that research does not exist on the efficacy of using word walls in a classroom. We agree. As reading teachers, we always have a word wall. We were always taken aback when identifying and explaining the initial phoneme/grapheme correspondences in words like thumb or phone. If word walls exist in classrooms across the country and cannot accurately represent every phoneme in the English language, it only stands to reason we evolve to something far more accurate. However, having a classroom sound/spelling wall just for the sake of having a sound wall is not right, either.

Challenges and misconceptions

Several years ago, when we first began teaching the knowledge base behind the proper use of sound walls, we were met with some unexpected challenges and misconceptions that still rear their heads today. Along with our Kid Lips colleagues, we believe that what led to most of this incorrect and improper implementation was the downloading of material from popular teacher websites that, in essence, took our framework, modified some of the material, and offered it to the population at large without teaching or explaining the WHAT, WHY, or HOW of sound/spellings walls. So, rather than calling out these misgivings, let us describe the correct setup and use of a sound/spelling wall.

Sound walls are sound/spelling walls that can reap huge rewards when appropriately utilized in a classroom. Here are two key features:

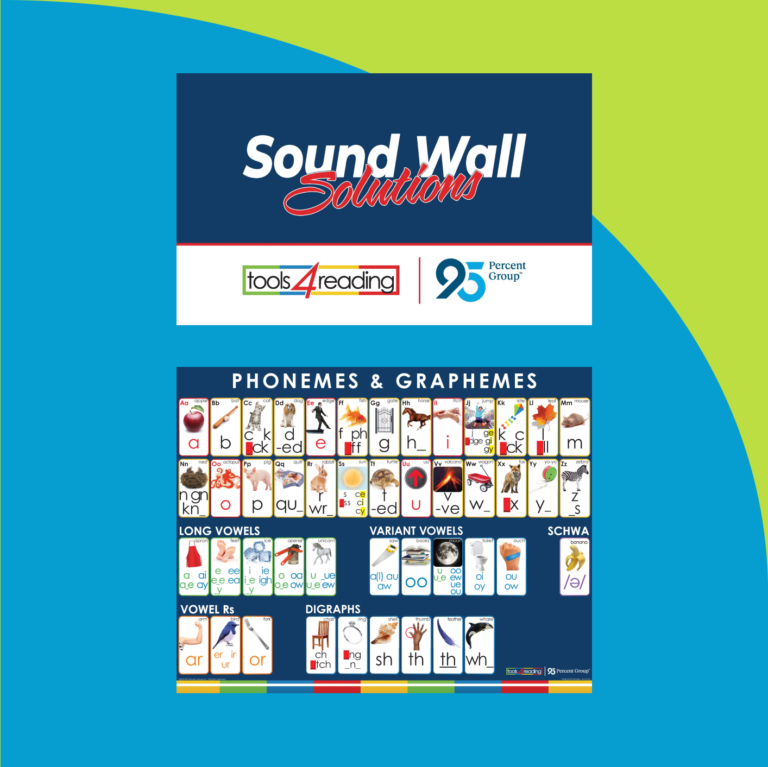

#1: Consonant sound/spelling walls that are organized and labeled according to placement and manner of articulation (Fromkin, Rodman, Hyams et al., 2017).

- This organization can help teachers determine which phonemes are easier to produce because of where they are produced in the mouth (IDA Phoneme Awareness Fact Sheet, 2022).

- These labels and the organization of the sound/spelling walls can assist the teacher in providing phoneme articulatory descriptors when needed.

#2: Each column and row is framed to better demonstrate the placement and articulation of each phoneme and show that paired phonemes only differ according to the activation or deactivation of the vocal cords.

#3: Vowel sound/spelling walls that are labeled with appropriate descriptors

- Both sets consist of:

- Mouth picture cards that serve as visual cues

- Keyword/grapheme picture cards also serve as visual cues representing any given sound with the most common grapheme representations for the targeted phoneme.

#4: Content area words or words that represent targeted phonics skills placed on the wall with corresponding phoneme/grapheme representation.

Let us reiterate: along with our Kid Lips colleagues, we believe the cause for many misconceptions is the lack of a solid knowledge base behind sound/spelling walls. We took great pride in writing an instructional guide for teachers that explains the features of any English phoneme, tips for teachers to apply during instruction, an instructional sequence to help deliver instruction, and cross-linguistic connections between English and Spanish. The cross-linguistic connections help teachers support the linguistic repertoire students bring to the classroom or explain how to articulate phonemes that simply do not exist in a student’s home language. Imagine being a native Spanish speaker and having to learn nine new English vowel phonemes and internalize that some vowel phoneme/grapheme representations differ from how they were taught in their home language! The information found in the instructional guide explains this and more.

Let’s enhance knowledge and instruction (to improve implementation of the Sound Wall concept)

Based on what we had learned from Dr. Moats, our years of experience as instructors and interpreters of published research, and the basic fact that the 26 letters of the alphabet cannot possibly represent all the phonemes of the English language, it seemed logical to move towards something that made more instructional sense. However, because many sound/spelling walls are being improperly utilized, it is unfair to throw the entire concept under the bus. We are dedicated and knowledgeable educators who have written instructional support that can dramatically improve instructional practice when presented through professional learning. We agree with the critics who state that displaying mouth pictures alone is insufficient. We never said it was!

A study published by Ehri and Boyer (2011) also caught our attention. Their work aimed to improve the understanding of two previous studies (Wise et al.,1999; Castiglioni-Spalten and Ehri, 2003) that affected overall word reading abilities. While our original research platform was primarily informed by the work of Liberman (1998, 1999) and the role of linguistically specialized articulatory movements that contribute to the overall perception of phonemes, Ehri and Boyer’s finding convinced us of the necessity to incorporate grapheme representations into our approach. This transition from word walls to sound walls to sound/spelling walls was a direct result of Ehri and Boyer’s work.

Ehri and Boyer’s (2011) study yielded significant findings. It demonstrated that phoneme segmentation training, whether conducted with letters alone or in combination with articulatory pictures, was effective in helping young preschoolers develop phonemic spelling skills. Moreover, the inclusion of articulation in letter segmentation training was found to enhance children’s reading ability compared to letter-only training. This suggests that teaching articulatory features may facilitate access to the motoric gestures that form phonemic representations of words in memory. Consequently, during the word learning trials of their study, letters in words became more firmly associated with these motoric phonemic constituents, thereby supporting word reading. However, the same benefits were not observed in nonword repetition. These findings have significant implications for our resources and further research.

Helpful insight from the International Dyslexia Association

Shortly after the Kid Lips instructional guide was published, the International Dyslexia Association (2022) published a fact sheet titled “Building Phoneme Awareness: Know What Matters.” The fact sheet states that focusing students’ attention on the articulatory features of a phoneme can be beneficial for fostering awareness of individual phonemes. Even with the slight variation in lip position of the articulation of /z/ in zebra and zoo, students can notice the key articulatory components, such as the effort it takes to push air through the front teeth that are slightly touching and the activation of the vocal cords. Because of the strong evidence supporting the incorporation of graphemes in phoneme manipulation tasks, after a quick and explicit (no more than five minutes) phonetics lesson, a teacher can place the words zebra or zoo under the “z” grapheme. This approach ensures reinforcement of the phonetic structure of the /z/, enhancing phoneme awareness and the connection to print, thus supporting word reading development. Students can practice the skill taught by reading the target words before or immediately after being placed on the wall. To further promote language development, teachers can use the target words to form complete sentences that students can read.

For a Sound Wall to be effective, proper training is essential

Sound/spelling walls are tools teachers can use to support phoneme awareness and, ultimately, literacy development. However, like any other tool, whether mechanical or a resource to a curriculum, the user must receive the proper training and coaching to ensure its appropriate use. Sound/spelling walls must be seen in the same light. It concerns us when material is downloaded from teacher resource websites and used in a classroom without knowing the “why” and “how” behind it. Our concern is far-reaching and extends beyond just sound/spelling walls. The instructional know-how needed to use sound/spelling walls in any classroom properly is not over-the-top, but it is necessary to ensure over-the-top results.

Learn more

Ready to dive deeper into the transformative potential of Sound Walls in enhancing literacy instruction? Explore further with 95 Percent Group to unlock valuable resources and training for maximizing the effectiveness of Sound Walls in your classroom.