Reading comprehension basics: Types and strategies

A post from our Literacy Learning: Science of reading blog series written by teachers, for teachers, this series provides educators with the knowledge and best practices needed to sharpen their skills and bring effective science of reading-informed strategies to the classroom.

Reading comprehension is the ultimate goal of learning to read. It’s also considered an outcome of teachable foundational reading skills for a reason. Reading comprehension could not be more important! The ability to understand what one is reading takes people from surface-level readers to insightful and critical thinkers.

According to a National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) survey, 43% of adults have trouble with basic reading comprehension while analyzing dense text, making it all the more important to teach reading comprehension accurately to students as they learn to read in school. This in-depth guide to reading comprehension will explore the building blocks of the skill and strategies for how best to teach it in a classroom.

What is reading comprehension?

Reading comprehension is defined as the ability to deeply understand and grasp text using prior knowledge, educated analysis, and predictions, among other techniques. Without reading comprehension, sentences are just words on a page without any further meaning. Properly teaching students to comprehend what they read gives them the ability to engage more deeply with the text they’re reading. It is a pillar of learning to read, which makes it both a goal of reading and the consequence of proficiency in the other four pillars: phonemic awareness, phonics skills, reading fluency, and vocabulary.

Why is reading comprehension important?

Reading comprehension transforms the reading process for students. It gives students the power to analyze and understand the text they’re reading, helping them to form their own opinions and questions. Being proficient in reading comprehension creates lifelong learners. Those who grasp and understand the complexities of reading comprehension not only see academic success but see success outside of the classroom in their professional careers, social lives, and beyond.

Comprehension is the outcome of reading. It’s the goal of reading. It’s what we’re trying to attain in the classroom as we’re teaching and guiding our students.

Diana Betts

Who struggles with reading comprehension?

Reading comprehension is a higher-level multi-dimensional reading skill, and therefore, more difficult for many to understand. Since it requires a firmer grasp of the other foundational reading skills, struggling with those other building blocks of reading will make it even more difficult to develop high reading comprehension skills. While teachers begin introducing students as young as kindergarten to reading comprehension through educational lessons, as well as activities and games, this is a reading skill that will need continual instruction over time, especially among younger readers. A lack of proper teaching strategies could lead readers to struggle with the ability and impact their future desire to read.

Students with reading disabilities may struggle with reading comprehension. Those dealing with challenges such as dyslexia and dysgraphia may already be facing difficulties when it comes to recognizing and writing letters or words. That, in turn, can lead to slower reading abilities and cognition, impacting comprehension skills. If students have not been diagnosed with a reading disorder but are having a particularly hard time, it could be a sign to have them screened.

The building blocks of reading comprehension

There are four key building blocks to reading comprehension: decoding and fluency, vocabulary development, text structure and features, and background knowledge. Many of these are part of the foundational reading skills necessary to create confident and strong readers. Mastering these building blocks is an essential step toward mastering reading skills.

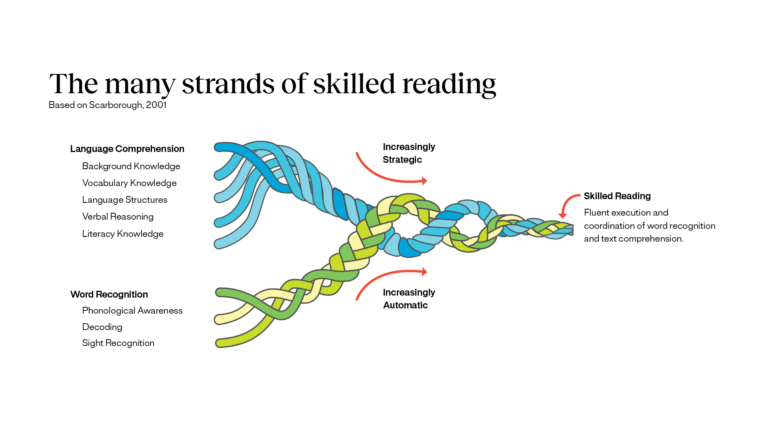

As a former classroom teacher (K-6), Dr. Diana Betts explains she always goes back to the Simple View of Reading and Scarborough’s Rope when considering the building blocks of reading comprehension. The Simple View of Reading is the belief that decoding skills alongside language comprehension are the key necessary for reading comprehension.

For Scarborough’s Rope, the theoretical model by Dr. Hollis Scarborough breaks down reading skills as two strands of a rope: word recognition and language comprehension. Based on the research, students in kindergarten through second grade need to learn to decode so they can move toward a full understanding of everything they’re reading. After learning the word recognition skills then they can continue working on the strand that’s all about language comprehension.

Decoding and fluency

One aspect of having strong reading comprehension is the ability to decode words and read fluently. Decoding is the ability to break down words by understanding the connection between letters and sounds. Studies have shown that decoding is vital for young students to learn to read. Fluency and decoding go together. If readers are having trouble decoding, then they will have trouble reading more effortlessly.

“Fluent readers can read connected text with accuracy, automaticity, and prosody,” explains researchers in a study on the relationship between reading fluency and reading comprehension skills in second-grade students, “Without practice, automaticity cannot develop in reading, and readers must focus their attention on decoding, limiting their ability to simultaneously comprehend.”

If students are struggling with decoding, there are different decoding strategies for teachers to use to help students improve their skills. Explicit and direct instruction is one key method such as the ‘I do, we do, you do’ approach. This simple method first has the teacher show students what they’re doing, then the students take part with guidance and monitoring by the teacher, and finally each individual student tries it. It comes down to making sure students are appropriately supported and scaffolded in their level of understanding.

“In those younger grades teachers are doing a lot of modeling, and then as we move on that responsibility shifts,” explains Dr. Diana Betts. “It should end with higher student responsibility. By the end of a comprehension lesson or strategy instruction activity the goal is that students are doing the work independently.”

Vocabulary development

Another backbone to reading comprehension is vocabulary. If students don’t have a broad and cohesive vocabulary, it will be harder for them to comprehend what they’re reading because that time will be spent trying to make sense of the meaning of the words within the text, instead of the broader meaning. Research has shown that readers need to understand 90-95% of the words they’re reading to accurately comprehend it.

Vocabulary needs to be regularly taught in the classroom for students to build their knowledge. It’s also not just about learning words and their set definitions but teaching students how to recognize and learn words on their own. Students need to learn how to recognize common affixes and roots to grow their vocabulary skills. Routine instruction is key. Our 95 Vocabulary Surge™ provides resources for teachers to spend 15 minutes each day working on vocabulary in the classroom using strategies like manipulatives, word lists, and worksheets.

Text structure and features

The way sentences are written and how they work together within the whole text is referred to as text structure. Recognizing text structure is more than just knowing when a sentence starts and ends. The ability to see the underlying meaning in text structure is a key facet of reading comprehension.

With text structure, there are three main reasons something is written: to tell a story, to persuade someone, and to share important informational details. The way these are relayed to the reader varies. There are different types of text structure including:

- Description

- Chronological

- Cause and Effect

- Problem and Solution

- Compare and Contrast

When readers understand text structure, they have a better ability to comprehend the text because of their ability to both logically and physically understand the text they’re reading. Logically, proficient readers will be able to gather a deeper understanding from the internal structure of ideas. Physically, readers are also able to use features in the text such as headings, subheadings, and a table of contents as context clues to make better connections about what they’re reading.

Explicit instruction of text structure helps students retain a deeper understanding of the text they’re reading, making it easier for them to not only understand the text but anticipate and predict what will happen next. Some teaching strategies when it comes to text structure include breaking down stories using graphic organizers such as a Venn diagram or story maps. This helps students make better sense of the text. Graphic organizers can help them layout the story in a visually appealing way while gaining a deeper understanding of the text.

Background knowledge

Background knowledge is the information readers use from past experience to better understand the text they’re reading. Study after study has shown that the more robust the background knowledge, the better students are able to comprehend a wide variety of topics and texts.

Background knowledge includes knowledge of words. This is not just the definition of a word, but understanding the context in which it is used. For example, if someone came across the word “bark” within a sentence, it could mean different things. If the story is about a dog, this could be the sound the animal is making. However, if this is a piece about trees, then this could be describing what makes up the trunk of the tree.

Background knowledge is more than just context; it also includes knowledge of the world in general. Similarly, making sense of phrases such as metaphors and idioms can be assisted with background knowledge.

There are multiple strategies to help readers build upon their background knowledge. While it might seem best to introduce students to as many topics as possible, it’s important to slowly introduce students to topics over time so they can grow in their depth of knowledge. One of the most important ways to build background knowledge is through wide and varied reading in the form of read-alouds. There are other specific activities that can be employed to build background knowledge, such as pictures, videos, or tapping into language. For example, teaching students to recognize nouns connected to specific categories (i.e. think of having students list words such as types of animals) or through comparing and contrasting words.

Reading comprehension strategies

There are 7 research-backed strategies (often referred to as processes) to help students grow their reading comprehension skills. These seven strategies are:

- Connecting

- Predicting

- Questioning

- Imaging or Visualizing

- Inferring

- Determining importance

- Synthesizing

For young students, these strategies are first taught through techniques such as modeling, but as students age, educators can turn to more explicit instruction. As students become more fluent readers, they’ll be able to interchangeaby use these strategies using different ones for different circumstances. This gives them a greater understanding of the text before, during, and long after they’ve finished reading.

Ahead is a breakdown of how educators can use some of these strategies to help students from the moment they begin reading to after they finish reading a piece of text.

Connecting

Connecting is the ability and skill to turn the text from something that’s being read to material that means something to the individual. Connecting to the text often evokes empathy and excitement, which can create a passion for the text, and therefore, a better desire and ability to comprehend what’s being read.

Before reading: Ahead of reading the text, use aspects like images, the title, and the author for students to look for a connection. If the story is about a cat, do students have a cat at home? If the author is Dr. Seuss, have students use their background knowledge. Have they read and liked books by him before? Maybe the main character is playing basketball, is that something they’ve played or seen played in the past? Helping students find ways to connect to the text even before reading it will get them excited and inspire them to connect with it.

During reading: Students then need to find opportunities to connect with the text while reading it. Have them examine the protagonist to see if there are qualities in them that students see within themselves. Has the book taken place in a spot that’s familiar to them such as a school or a park? These connections will help them better visualize parts of the story, relate to it, and therefore, connect with it.

After reading: Once the text has been read, there are still connections to be made. One critical way to think about the story is to connect it with previous books. Maybe the story mirrored The Ugly Duckling or Humpty Dumpty. By making connections or recognizing major differences between the text and others that have been read, students can better understand the story.

Predicting

Predicting encourages readers to go beyond the text they’re reading to make assumptions and expectations about what is coming next. In the context of reading comprehension, students need to think critically and problem solve using building blocks such as background knowledge, vocabulary, and text structure to decide where they think the text is heading. This keeps students engaged in the text they’re reading and encourages them to look beyond the surface-level story by coming to their own conclusions.

Before reading: Have students use everything they have access to make their predictions about what they’re about to read. If they’re starting a brand new book, have them examine everything outside of opening the book. Have them predict what they’re going to be reading based on the title of the book, the book cover, the description on the back, and the author’s name. Have students complete sentence stems such as “I predict that the character will…” or “I think this story will be about…” to help students scaffold their thinking.

During reading: While reading, have students stop and review what they’ve read so far. Who is the protagonist, where is this taking place, and what has the person done so far? Students will need to use context clues within the text, images (if the book has them), chapter titles, and the table of contents, to determine what will happen next within the story.

After reading: Once the reading is complete, students can continue to make predictions. While there may not be explicit answers (unless there is a second book), students can still be encouraged to predict where this story will continue. They can predict future trials and scenarios for the protagonist and antagonist.

Questioning

Questioning is the process of becoming a critical thinker by going beyond the text. This will help a reader better understand what’s beyond the text, question why certain things were written, and to create independent opinions. Questioning moves the power from the text to the reader, encouraging students to look past the words of the text and stand firm in their own thoughts.

Before reading: First, encourage students to ask questions about what they’re reading. This will help them with their predictions of what will be happening within the text. If it’s a picture book of a bird falling out of a nest, they may ask why the bird has fallen, if it will be able to fly, or how it will land. Have them write out their questions and search for the answers while reading the story. This will help them better understand the story and pay close attention as they move through it.

During reading: Pause while reading to ask students about the story. Before a page turn or at the end of the chapter, ask students what questions they have about the characters, the way they look, or the actions they’re taking. Sentence stems teachers can consider asking their students include “I wonder why the character…” or “What does the author mean when they say…”.

After reading: Use the time after reading to get students to question what they’ve just read. Did they learn a lesson? If so, have students question why the author wanted to share this lesson. Have students consider the way age, relationships, or cultural groups were shown within the story. Encourage students to think critically about the text and to ask questions about things that weren’t answered within the piece.

Imaging or Visualizing

Imaging or visualizing is a part of the reading comprehension process where readers turn the text that they’re reading into pictures within their minds. Research shows that students who visualize the words they’re reading at any point of the process (before, during, and even after) have better comprehension than those who don’t. Visualizing can be done mentally, but teachers can also encourage students to physically draw what they see within their minds after reading the text.

Before reading: Visualizing text before reading assists with the prediction process. By envisioning what students are about to read, they’re engaging their minds to make informed guesses about where the story will go and how it would proceed if they were the author of the story.

During reading: While reading, visualizing is a strong method to better make sense of the text that’s being read and to bring it to life. Instructors can use sentence stems such as “When I read this part, I picture…” or “I can imagine this setting as…”. By interpreting the text and creating images within the mind, students turn text into more than words and make it their own. This added interest can help students better comprehend the text.

After reading: After finishing the book or passage, students can use the power of visualizing to retain the words and story they’ve read. Visualizing is a powerful tool for students to use to replay passages they read in their minds, assisting in further analyzing and digesting the text.

Inferring

Inferring is the process of recognizing and understanding something that’s not clearly laid out within the copy. While it may seem similar to predicting, inferring is an entirely different reading comprehension strategy. The end goal of both predicting and inferring is coming to a conclusion, however, while predicting is about determining what is set to happen in the future, inferring focuses on deducing something that’s not explicitly stated. Being able to make inferences helps students grow in their ability to have a deeper understanding of text, grasping more within the story even if the author doesn’t write it word-for-word on the page.

Before reading: Have students examine the cover of the book and make inferences about the setting and characters. If it shows a couple of friends walking with umbrellas, rain, and a mud puddle, ask students what they are inferring about the weather. Or, if the main character has on a big winter coat, ask students what winter coats often signify and help them infer that the story is most likely taking place during the wintertime.

During reading: Teachers can consider doing a read-aloud of the text and provide their own inferences while reading through the story. For example, if it mentions that a character has their fingers curled up tight into fists, explain to students how they can infer that the character is most likely angry or upset about something.

After reading: After completing the reading, it’s a good time to ask students open-ended questions to encourage them to make inferences about the story and the author behind it. Have students infer why the author included certain objects and what they may have symbolized within the story, as well as the message the author may have wanted people to take away after reading it.

Determining Importance

To truly comprehend the text that’s being read, students need to be able to understand the main point of it. That’s where determining importance comes into the picture. This is the ability to accurately summarize the text and focus on key details. After reading a story, students should be able to tell someone who has never read the piece about the clear, important parts of the narrative.

Before reading: Before reading, have students summarize what the text will be about by using predictions they’ve put together. Determining the importance about the text before reading challenges students to create a simple summary as they read without getting bogged down in the details of a story.

During reading: On a simple level, this can be done by having students describe what happened within a chapter and highlight the most important part of the text. But this can also be taken deeper, by requiring students to look beyond the copy and come up with deeper reasons why the text was written such as focusing on the theme or important message the text is trying to send.

After reading: The challenge after reading will be to summarize the main point concisely and show students have clearly understood the most important points of the piece. Have students answer sentence stems such as “In summary, the author wants us to know that…” or “The story is mostly about”.

Synthesizing

Synthesizing in the context of reading comprehension is the ability to explicitly understand what has been read and interpret how that information is part of the bigger picture. After reading a story, students should be able to tell someone who has never read the piece what it’s clearly about and how it’s influenced or changed their perspective on the topic.

Before reading: Before reading, have students discuss what background knowledge they have and predict how reading this text could impact or influence thier facts or experiences. Synthesizing before reading challenges students to review what prior knowledge they have about the topic and prepare for how the text could change what they know about it.

During reading: Have students examine how the text compares to what they initially thought or knew about the topic ahead of reading. Encourage students to recognize how ideas around the topic are evolving or changing from before they started reading up until this point.

After reading: Once students have finished reading, they can then synthesize what they have read and reflect on it. Instructors can have students answer questions such as “What is something new you have learned from this piece?” and “How did the story change what you previously knew about the topic?”.

Assessment of reading comprehension

There is not one sole assessment that is used to track reading comprehension. Because the skill is so multidimensional there are different methods used to track student progress. There are simple informal ways within the classroom to check and see how students are managing their skills, along with more formal exams solely designed to test student reading skills including reading comprehension.

Checking for reading comprehension in the classroom

Informally in the classroom, a method that is backed by multiple studies is read-alouds. Having students read stories out loud is known to help students practice and improve their reading comprehension skills. Teachers can also use the “I do, we do, you do” strategy to ensure students are truly gaining an understanding of how it works.

“Teachers can’t physically see what the child is thinking. They’re truly relying on oral and written output which can make assessment challenging,” describes Dr. Diana Betts. “That’s why activities like retelling are important. The teacher can model a read-aloud and what the expectation is in an oral response.”

Another way to assess reading comprehension is to have students complete graphic organizers while reading through text. Students can use these to break down the main point of the story, separate the details, and put together a concise summary. These can help them really organize their thoughts.

Within exams, a common test question is to have students read a paragraph of text and to check comprehension by having students choose a correct summarization or inference about it. This can be done with multiple-choice answers and also with open-ended questions.

Reading comprehension tips

Reading comprehension can be worked on individually and with the help of others such as teachers and parents. Multiple perspectives and guidance will help students grow in their reading comprehension skills, but it requires time and energy.

Tips for teachers

- Try a reciprocal teaching strategy by having students each do one reading comprehension strategy while reading a story. So, have one student summarize what was read, one asks questions about the content, one describes what the imagery is within the piece, another predicts what will happen next, and one describes how this text relates to them.

- Discuss stories together before, during, and after reading to encourage critical thinking.

- Use cooperative learning strategies. Have students partner together to work on predicting, clarifying, questioning, summarizing, and connecting with a piece of text.

- Practice reading stories aloud together – be sure not to rush!

- Do engaging reading comprehension-based games and activities together such as a puppet show story retelling

- Go on educational field trips (i.e. museums, gardens, zoos) to expose students to new topics and experiences to grow background knowledge

Tips for students

- Go to the library and choose two books: something you’re already passionate about and another on a subject you’re interested in, but haven’t read much about to work on growing their background knowledge

- Fill out story maps or graphic organizers while reading a story

- Draw pictures depicting what you’re reading

Conclusion

The ability to fully comprehend a text transforms students from passive readers to critical, engaged thinkers. The process of building reading comprehension can take time, but once students grasp the ability to glean meaning from text, they’re set up to be lifelong learners. 95 Percent Group is a firm believer in teaching the building blocks of reading comprehension to create strong, future readers.

Download this free 3rd grade reading comprehension worksheet to start building out your comprehension strategies and teaching methods. 95 Percent Group has designed a Tier 2 intervention called 95 Comprehension, Grades 3-6 to help students grow in their reading comprehension skills in small groups. Learn more about this evidence-based program or you can directly purchase the reading comprehension program in our online store.

Expert biography

Diana Betts, EdD, early literacy expert

Regional consultant manager, 95 Percent Group

Dr. Diana Betts is an assistant professor and program coordinator of literacy and reading at Gardner-Webb University, as well as a regional consultant manager for 95 Percent Group. She is also a former classroom teacher (K-6) and media coordinator. Dr. Betts is an expert in early literacy, program evaluation, professional development, and higher education.

Sources

- Snow, C. (2002). Reading for Understanding: Toward an R&D Program in Reading Comprehension. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Juel, C. (1988). Learning to read and write: A longitudinal study of 54 children from first through fourth grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(4), 437–447.

- Gough, P.B. & Tunmer, W.E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7, 6–10.

- Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice.

- Nagy, W. E., & Scott, J. A. (2000). Vocabulary processes. In M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, P. D. Pearson, & R. Barr (Eds.), Handbook of reading research, Vol. 3, pp. 269–284). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Anderson, R.C., & Pearson, P.D. (1984). A schema-theoretic view of basic processes in reading comprehension. In P.D. Pearson, R. Barr, M.L. Kamil, & P. Mosenthal (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (pp. 225–291). New York, NY: Longman.

- Kendeou, P., & van den Broek, P. (2007). The effects of prior knowledge and text structure on comprehension processes during reading of scientific texts. Memory & Cognition, 35(7), 1567–1577.

- Meyer, B.J.F., & Rice, G.E. (1984). The structure of text. In P.D. Pearson, R. Barr, M.L. Kamil, & P. Mosenthal (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (pp. 319–351). New York, NY: Longman.

- Ogle, D., & Blachowicz, C.L. (2002). Beyond literature circles: Helping students comprehend informational texts. In C.C. Block & M. Pressley (Eds.), Comprehension instruction: Research-based best practices (pp. 259–274). New York, NY: Guilford.

- Smith, R., Snow, P., Serry, T., & Hammond, L. (2021). The Role of Background Knowledge in Reading Comprehension: A Critical Review. Reading Psychology, 42(3), 214–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2021.1888348

- Alexander, P. A., Kulikowich, J. M., & Schulze, S. K. (1994). How subject-matter knowledge affects recall and interest. American Educational Research Journal, 31(2), 313–337. https://doi.org/10.2307/1163312

- Guerrero, A. (2003). Visualization and Reading Comprehension. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED477161.pdf

- Omar, A., & Saufi, M. (2015). Storybook Read-Alouds to Enhance Students’ Comprehension Skills in ESL Classrooms: A Case Study. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1121916.pdf