7 High impact, evidence-based reading comprehension strategies (processes) for educators

A post from our Literacy Learning: Science of reading blog series written by teachers, for teachers, this series provides educators with the knowledge and best practices needed to sharpen their skills and bring effective science of reading-informed strategies to the classroom.

Reading comprehension is considered the ultimate goal of reading instruction. While in the past, there was a belief that reading comprehension was based only on extracting meaning from the text, we now know that comprehension involves a reader using conscious processes to construct meaning based on both the text, and the reader’s own knowledge and experiences.

In her influential research study titled, “What Classroom Observations Reveal About Reading Comprehension Instruction (1978),” educator and researcher Dolores Durkin described reading comprehension as “the essence of reading.” It truly is the reason we read—to make meaning from the words.

Strategies v. processes

One thing to note is that although we often refer to these instructional methods as reading comprehension strategies: reading comprehension is the result of many different simultaneous processes. In 95 Comprehension Grades 3-6, we use the word processes instead of strategies to emphasize that these things are happening while readers are reading. Strategies are considering ongoing processes, and the goal is for teachers to guide students to be aware of and use these processes so that they will eventually be able to discern between them, and use them, on their own.

Dr. Diana Betts, early literacy expert and regional consultant manager with 95 Percent Group, underscores why this is the correct language to use when discussing reading comprehension.

“Reading comprehension is an ‘in the head’ process.” Betts explains. “In order to measure it, or provide guidance to students, we can only point to artifacts [student output—whether verbal or written] to see what’s happening inside the reader’s mind.”

The nuances of explicit reading comprehension instruction

Strategies guide the reader to pay attention or to manage [working] memory in ways that increase learning. The use of comprehension strategies needs to be flexible, and suitable to a few things: a reader’s goals, the demands of a specific text, and the actual challenges being confronted.

Diana Betts, EdD, early literacy expert | regional consultant manager 95 Percent Group

Explicit reading comprehension instruction is essential for developing strong and independent readers. By directly teaching students specific strategies for understanding the comprehension processes, educators equip them with the tools necessary to navigate complex materials and construct meaning effectively. This approach is key because while proficient readers often employ these strategies automatically, struggling readers may lack the skills to do so without guidance. Through explicit instruction, teachers can bridge this gap, ensuring that all students have a conscious awareness of the strategies available to facilitate deep comprehension.

It’s worth noting that the effectiveness of explicit reading comprehension instruction lies largely in its structured and scaffolded approach. Betts weighs in on this idea. “Teachers guide students on when to use strategies and for what purpose. There are strategies for pre-reading, during reading, and after reading.”

Steps for explicitly teaching comprehension strategies: “I do, We do, You do”

- Direct explanation (“I do”): the teacher explains why the strategy helps students comprehend what they are reading, and when they should use each strategy

- Modeling: the teacher models how to effectively use the strategy—usually achieved by reading and thinking aloud to make the thinking visible

- Guided practice (“We do”): the teacher works with the students, assisting in their understanding of how and when to apply the strategy

- Independent practice/application (“You do”): the teacher facilitates students in applying the strategy on their own and is available to offer feedback as necessary

By following a systematic process, teachers can gradually transfer the responsibility and ownership of strategy use to the students; the goal being high student agency and ownership over their reading comprehension practices.

This “gradual release model” allows learners to internalize the strategies and apply them flexibly and as needed across various texts and contexts. As students become more adept at using these strategies independently, they develop the skills necessary for self-monitoring their comprehension, adapting their approach when faced with challenges, and ultimately becoming more confident and capable readers.

Here are the researched-based reading comprehension strategies you need

Deep reading comprehension requires the simultaneous use of several strategies. “Effective readers are able to choose and adapt strategies as a particular text or reading task demands,” Betts clarifies.

“The goal is for students to be able to utilize their ‘cognitive toolbox’; to ‘reach in’ and select a tool or strategy to help them based on the specific reading demand they are faced with,” Betts continues. “Because this is the ultimate goal, teachers not only need to teach multiple comprehension reading strategies, but they also need to teach the context within which students may need each—so students can find flexible ways to apply the strategies independently.”

Teachable reading comprehension strategies can be divided into categories based on when it makes sense to engage in them. For most students, there are strategies they employ before they begin reading a text, while they are in the midst of reading, and then after they are done reading.

Below are 7 impactful strategies, grounded in science, that can first be modeled through read-aloud or shared reading for early learners, and then explicitly taught to older students for their own use while reading.

Activating prior knowledge

Activating prior knowledge helps students to anchor themselves in what they are about to read using what they already know about a topic. According to the Institution of Education Sciences (IES) and What Works Clearinghouse (WWC), who published a practice guide titled Improving reading comprehension in Kindergarten through 3rd grade, “Students think about what they already know and use that knowledge in conjunction with other clues to construct meaning from what they read, or to hypothesize what will happen next in the text. It is assumed that students will continue to read to see if their predictions are correct”.

At 95 Percent Group we represent this process as two strategies: connecting and predicting.

Connecting

When a good reader is connecting to a text, they are relating something they know to something they are reading about—connecting their own knowledge, life experiences, and texts they’ve previously read to the passage in order to better understand what they are reading. After reading a passage, ask your students if they can make any text-to-text, text-to-self, or text-to-world connections. Students will improve reading comprehension by connecting with something that they are already familiar with; making connections improves the likelihood that students will share their experience and show a greater interest in what they are reading. This strategy can be modeled for younger students during a shared reading as a think aloud, and taught to older students to use in their own reading.

Strategy type: Pre and during reading

Recommended grade level: 1st grade and above

Predicting

Predicting is another comprehension strategy that is done both before and during reading and looks different for each. When a reader makes a prediction they use both ideas from the text and their own background knowledge to make a thoughtful guess about what might happen next. Making predictions before beginning a text is a natural sequential step after previewing the text. A younger reader might use illustrations or the name of a story to make a pre-reading prediction while a more experienced or older reader might scan the subtitles or look at certain vocabulary words and anchor in their own background knowledge to help them predict what a text will be about. “It is assumed that a student will keep reading to see if their predictions are correct” (Shanahan et al., 2010). This strategy can be modeled for younger students during a shared reading as a think-aloud, and taught to older students to use in their own reading.

Strategy type: Pre and during reading

Recommended grade level: 1st grade and above

Questioning

Good readers use questioning to wonder about the words or ideas in something they are reading. When we ask questions about what we are reading we start with question starter words. The question starter words are: who, what, where, when, why, and how. By questioning words and ideas in a text, a reader can find out the information that helps to fill gaps or pushes them to think about something in a different way. Using sticky notes is a great way for readers to use this strategy during reading. Students can stop when they have a question and write the question on the sticky note—which can then be placed right on the spot they had the question about. This strategy can be modeled for younger students during a shared reading as a think aloud, and taught to older students to use in their own reading.

Strategy type: During reading

Recommended grade level: 1st grade and above

Imaging or Visualizing

Visualizing is a part of the reading comprehension process where readers turn the text that they’re reading into pictures or a movie within their minds. Research shows that students who visualize the concepts or storyline they’re reading about at any point of the process (before, during, and even after) have better comprehension than those who don’t. Visualizing can be done mentally, but teachers can also encourage students to physically draw what they see within their minds during or after reading the text, creating an opportunity for students to use a different part of their brain.

Strategy type: Pre and during reading

Recommended grade level: 1st grade and above

Inferring

Making inferences is figuring out what the author means but doesn’t say. Some describe it as “reading between the lines,” for this reason. Making inferences is a sophisticated comprehension process that can be guided in a more simple way with students that are ready for deep comprehension. When we ask students to infer, it means we are asking them to consider both what the author IS saying and what they already know to be true in order to consider what the author might mean above and beyond the text. It’s a “real world” strategy that not only deepens a reader’s capacity to reflect on what they’re reading, but also helps them to understand the nuances of their own lives.

Strategy type: During reading

Recommended grade level: 3rd grade and up

To push beyond a dry literal understanding, to add our own opinions, knowledge, and ideas—that is to infer.

Keene, E., and Zimmermann, S. 2007.

Monitoring comprehension or applying “fix up” strategies

Students pay attention to whether they understand what they are reading, and when they do not, they reread or use strategies that will help them understand what they have read (Shanahan et al., 2010).

Rereading Strategically

When a reader gets to the end of a text, often there will be parts that weren’t fully absorbed. This is especially true when reading nonfiction or informational text. Attending and attuning completely to everything in an informational text is difficult—especially for readers that are still learning how to discern and move between comprehension processes. This makes rereading different parts of a text a key strategy for ensuring full comprehension.

Determining importance

When we read, we are taking in a lot of information. There are a few skills that can be considered part of the process of determining importance: good readers use text structure and features, topics, key details, main ideas, story elements, and summaries to understand what they are reading. For a good reader, they are ultimately intertwined and used in a flexible and intuitive nature.

Strategy type: During/post reading

Recommended grade level: 3rd grade and up

Synthesizing

Synthesizing is when a reader develops their own idea about the message in a text by determining which information is important and combining the key ideas identified. Honing this skill allows readers to have a deep understanding of what they’ve read and an integration of this knowledge with their own experiences. It’s what we take away from reading a text and can apply to our own lives or situations. This is another strategy for which writing about what they’ve read can help a reader to know what new understanding they have from a text. This can also sometimes be a combination of summarizing or retelling, reflection, and making connections.

Strategy type: Post reading

Recommended grade level: [insert grade level]

Implementing reading comprehension strategies

Thinking aloud is the single most important teaching tactic at our disposal…Thinking aloud provides direct access to the reader’s (or writer’s) mind, allowing children to observe how understanding comes about.

Keene and Zimmerman, Mosaic of Thought (2007)

An important factor to highlight is the idea that readers need to be confident decoders before we can expect them to have cognitive space for comprehension strategy instruction. During the early elementary years (K-2), readers are spending all of their cognitive energy on building their word recognition skills, and while they might be running comprehension processes “in the background” already (depending on their individual capabilities), most students aren’t ready for this type of instruction until around 3rd grade.

Implementing reading comprehension strategies effectively requires a systematic and consistent approach. Teachers should introduce strategies gradually: briefly and explicitly modeling each one and providing opportunities for guided and independent practice as well as facilitating the students’ understanding when and how to apply them. Betts offered that one of the best ways to model comprehension strategies is by thinking aloud—to make thinking processes visible to students. Additionally, encouraging students to reflect on their strategy use and its impact on their understanding can foster metacognition and independent application. While regular assessment and feedback allow teachers to monitor progress and adjust instruction as needed, it’s important to remember that there are outside factors that affect comprehension “performance.”

Betts explained, “We can only point to artifacts to see what’s inside the reader’s mind, and processes can only be measured via written or oral expression. Because of this, a reader’s writing and speaking abilities will always influence their comprehension abilities and assessment.

Tailoring strategies for different age groups

As stated above, strategy instruction is most effective with readers that are 3rd grade and up. They need to be strong decoders before they have the cognitive space to engage more deeply with a text.

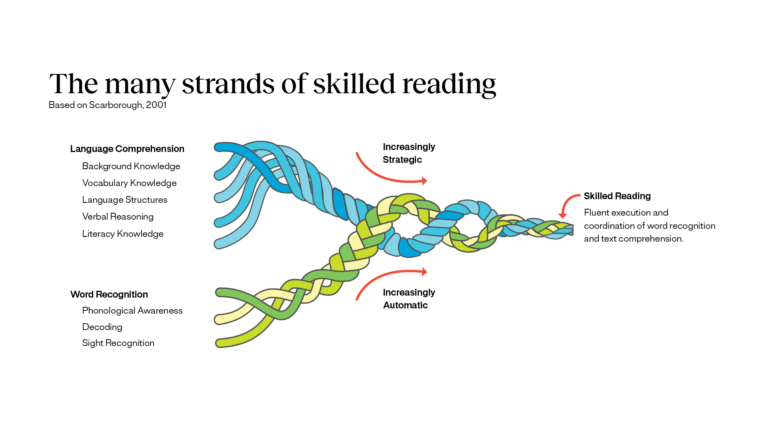

“For younger K-2 learners,” Betts said, “we must be sure they are strengthening their word reading abilities (decoding) first. Think in terms of Scarborough’s Rope—word recognition. If kids can’t read the words easily, they won’t yet have the cognitive room to focus on comprehension/text meaning. We also have to consider fluency for younger readers. Students need to be automatic and fluent to fully comprehend before comprehension is possible.” She continued. “K-2 learners will benefit greatly from read-alouds and teacher modeling of effective strategies. Since comprehension is not a naturally visible process, teachers rely heavily on written or oral expression to gauge comprehension.”

Here are some helpful tools for scaffolding comprehension instruction for all ages and learning differences:

- Graphic organizers

- Information text: text structures, text features, main idea + supporting details, double-sided note-taking for questioning and making connections

- Fiction text: storyboarding or plot mountains, character analysis charts, double-sided note-taking for making predictions or connections and writing about text excerpts

- Writing prompts: for reflecting, summarizing, and synthesizing

- Cooperative learning (groups, pairs, teacher guided, etc.) for reflective discussion

Conclusion

Comprehension is never all or nothing: it’s a A LOT of gray area. It’s multidimensional.

Diana Betts, EdD, early literacy expert | regional consultant manager 95 Percent Group

Teachers can offer their students brief, explicit modeling to make comprehension processes conscious and help them to understand when to use different strategies. And, these strategies have to be used often and flexibly in order to become adept at navigating them. “Good strategy users have strong content knowledge and are motivated,” Betts said. “They have strong metacognition, and are able to analyze reading tasks (comprehension monitoring). They have a large ‘cognitive toolbox’ of strategies to pull from.”

“Because of this,” she posited, “good strategy instruction attends to each of these things: it builds students’ background/world knowledge, builds student confidence with the strategies, develops students’ metacognition so they know when to use the strategies, teaches them how, when, and why to use many different strategies, and teaches students how to confidently and quickly choose the appropriate strategy.”

Expert Biography

Diana Betts, EdD, early literacy expert

Regional consultant manager, 95 Percent Group

Dr. Diana Betts is currently the Southeast Regional Consultant Manager for 95 Percent Group. She leads a team of consultants who provide professional development and coaching services to educators and administrators across the country in evidence-based literacy instruction. Prior to this, Dr. Betts worked in higher education as a professor of literacy. She was appointed to a Literacy Task Force for the North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities organization to support literacy outcomes at all educator preparation programs across the state in January of 2022. Dr. Betts is LETRS trained and has written undergraduate and graduate courses in evidence-based literacy instruction.

For 13 years, Dr. Betts worked in elementary and middle schools as a teacher, media coordinator, gifted specialist, and athletic coach. She believes that all children can become successful readers with the right instruction and support inside and outside of the classroom. In addition to classroom experience, Dr. Betts also worked as a computer science curriculum developer and coach. In this capacity, she helped write an integrated computer science curriculum for K-6 students and coached teachers in Florida and South Carolina in implementation.

Dr. Betts received her Bachelor’s degree in Elementary Education from High Point University, Master’s degree in Reading Education from East Carolina University, and doctoral degree in Education Leadership and Curriculum and Instruction from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington. She is a licensed classroom teacher, reading coach, school principal, and superintendent in both North Carolina and South Carolina.

Sources

- Baker, L. (1979). Comprehension Monitoring: Identifying and Coping with Text Confusions. Technical Report No. 145. Bolt, Beranek and Newman, Inc., Cambridge, Mass.; Illinois Univ., Urbana. Center for the Study of Reading., No. 145. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED177525.pdf

- Durkin, D. (1978). What Classroom Observations Reveal about Reading Comprehension Instruction. Technical Report No. 106. Reading Research Quarterly. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED162259

- Scarborough, H. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis) abilities : Evidence, theory, and practice. Handbook for Research in Early Literacy 2001 Guilford Press. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1573668924954702720

- Shanahan, T., Callison, K., Carriere, C., Duke, N. K., Pearson, P. D., Schatschneider, C., & Torgesen, J. (2010). Improving reading comprehension in Kindergarten through 3rd grade. In Mathematica Policy Research, IES PRACTICE GUIDE (NCEE 2010-4038). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED512029.pdf

- Willingham, D. T. & AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS. (n.d.). HOW WE LEARN. In AMERICAN EDUCATOR: Vol. WINTER 2006/07 (pp. 39–40). https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/media/2014/CogSci.pdf