Courageous leaders: The power of conviction, with Laura Stewart and Louisa Moats (part 1)

Laura Stewart, Chief Academic Officer at 95 Percent Group, spoke with author, speaker, and literacy advocate Louisa Moats, EdD, recently in the Courageous Leaders Webinar Series.

Here is their in-depth conversation about Dr. Moats’s lifelong journey to teach all children to read. Part 1 offers a remarkable exploration of pivotal moments in Dr. Moat’s career that have led to her courageous leadership in writing the groundbreaking book Speech to Print in 2000 and co-authoring LETRS® (Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling).

Laura Stewart:

We started this Courageous Leaders Webinar series in the fall because we wanted to elevate leaders in our field—to be able to tell their stories, and to honor their contributions to our profession and to our educators and our students. Our intention is to inspire you to take bold steps as educational leaders and to provide you with some practical tips for your own journey, wherever that might be.

I’m so excited to be in conversation with the one and only Louisa Moats. I’m sure for many readers, Louisa Moats needs no introduction. She is an educator. She is an author. She is a transformational leader, and I consider her a literacy hero. She’s been part of my journey in very profound and impactful ways. I’m very, very grateful for that, and I’m grateful that I have an opportunity to chat with her.

Trusting the twists and turns on the journey

Laura Stewart:

Let’s start by having you tell us about your journey as an educator.

Louisa Moats:

Well, it’s been a very long one, and it has involved a very unusual path in many respects. Sometimes when I ask myself why I know certain things, and have been persistent about advocating for certain ideas and practices—especially teacher education and teacher knowledge which have been my passions all along—I realize that I’ve been very fortunate to have gone from being a music major in college to the present, facing my eightieth year next year. Believe it or not, folks, that’s what’s happening.

I have had the experience of being a researcher working with the top researchers in our field, had the experience of being a clinician and meeting kids and adults who struggle with reading day after day for 15 years, and seeing that, I’ve had the experience of being in the classroom myself as the responsible teacher, feeling inadequate, helpless, and ineffective, which was where I started. And I’ve had the experience of being responsible for teacher education.

I’ve never come through the typical path that a lot of my colleagues have gone through, which is, after my doctorate getting into a university position and having to operate within the constraints of that. I have taught in universities, but never as a full time employee. So we had to do all these other things. And I feel very fortunate that I have this unique path—you could call it a checkered career or you could call it a very interesting career path.

Laura Stewart:

You have to tell us, how did you get from music to education? This is an interesting twist in your journey.

Louisa Moats:

Well, it was an indirect route. At the end of college I went to Wellesley College as a music major, not having a clue what I was going to do. I was 21, not married, and I needed a job so I went to secretarial school, learned how to type and take shorthand, and got hired as the secretary in a neuropsychology laboratory that was just being set up in Boston. It was a very young discipline then in 1966. There was no pediatric neuropsychology as a field, even at that point. So in a clinic my boss put a robe on me and said, “You can learn how to give the neuropsych test as long as you still type the reports.”

And I thought, “Okay, that sounds like an interesting thing to do.” I had two years of experience with neurology patients of all ages, because my boss was so supportive. He would send me and the other lab techs to neurology rounds where cases would be discussed by the medical personnel. For example, he sent us to the brain seminar that was run over at Harvard by Norman Geschwind. The IDA named an award after Norman Geschwind. I actually heard him give case presentations in grand rounds at Harvard, all because my boss just thought that we young women who were giving the tests should understand more about what we were doing.

Then he kicked me out the door, saying, “You need to get a master’s degree. I know this fellowship program that they have down there at Vanderbilt. So apply for that, please. And once you’ve gotten a degree, maybe you can come back here and work.” So that actually did happen. I went to Nashville.

Laura Stewart:

When you look back at that time, do you think about the twists and turns, and how all those pieces came together to lead you in the direction you went?

Louisa Moats:

Yes. And if anybody thinks that I started out in this field with a clear idea of what I wanted to do, what I wanted to become, what I wanted to accomplish, that would be seriously mistaken. It was more a matter of following my nose, developing a passionate interest from the time in the neuropsych lab which was just such a wonderful orientation. If you are a teacher, to be able to think about that child in front of you in terms of the neurological processes that have to be developed and supported for that child to learn—to have an idea of how the brain functions, how the learning process occurs, how the language systems of the brain work, what the signs are of things not being wired up well—to have that in the beginning, and to carry that with me all through my career has been a terrific blessing and asset.

I’ve just been very lucky that I’ve had people in my life who have been fabulous mentors. I can’t say enough about the importance of mentorship, for all of us in our lives.

Pivotal moments

Laura Stewart:

The work in the neuropsych lab was a pivotal moment in your career. Can you name some other pivotal moments?

Louisa Moats:

There are a lot of them, some of them fairly drawn out, some of them just real Aha moments. I think the first real Aha was when I got into the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and I did that because I had gone back to work in the neuropsych lab as the education specialist. About three months into the job my boss said to me, “By the way, this job is described for someone with a doctorate or doctoral level training, or someone who’s enrolled. So you will not be able to keep this job unless you enroll in a doctoral program.”

It wasn’t like I was thinking I’m going to get a doctorate. It was that he told me I had to. So I thought to myself, “Well, I’m living in Cambridge. Harvard’s down the street.” I didn’t understand that Jeanne Chall and her reading department were pretty special. I didn’t really get it, but I applied. They took me and I’m extremely glad that they did, because that’s when I began to really learn something,

Before that, as an educator I had been very aware that I didn’t know enough to do a very good job, that I was always covering up for what I didn’t know. I was always insecure. As we’ve often talked about together, and as my colleagues and I have often talked about, when you don’t know what you don’t know you just have this feeling of being kind of lost and ineffective, and you doubt yourself, but you don’t even know how to put that into words, or how to think about what it is you don’t know.

Aha—Introduction to Language course with Carol Chomsky

So the Aha moment for me was getting into the required Introduction to Language by Carol Chomsky, Noam Chomsky’s wife. I thought “Oh, I know all about language, right?” The class had a pretty heavy duty textbook, and I began to think “I don’t know anything,” but a real Aha moment was when she started teaching about phonology and the speech sounds of English, and I realized, “Oh, my goodness! Now I see what this print system is representing!” Before that it was always kind of a befuddling mystery, because most reading programs are set up to teach from print to speech—and this debate is still going on now.

All of a sudden it was like this light shining into my brain: “Aha! Now I can make sense out of how this works, because I’ve learned what the speech sounds are, and not just that, I’ve learned about the system of phonology, the way in which these speech sounds either are alike or different, how they contrast, and all that. And all of a sudden then I could understand what this whole thing about phoneme awareness meant because at that point the early work of the Haskins Lab on phonemic awareness as the critical preparation for learning to read was being taught to us. It wasn’t widely known. We had connections at Harvard, so we were getting lectures by Isabelle Liberman and learning about phoneme awareness and its role. And I began to understand.

Carol Chomsky also started applying what she was teaching us to understanding and explaining children’s spelling errors, and that too was an Aha because I had spent those years in the clinical setting, looking at kids’ spelling and thinking, “Oh, there’s a lot to get out of this.” But I didn’t have the clarity of thought and the basis of language knowledge in order to get it and interpret.

Eventually I did my dissertation, and went on to do several studies that were published, and then wrote Speech to Print, which has a lot about that. But that experience in Carol Chomsky’s class was life changing for me, definitely.

Aha—Reid Lyon and NICHD

Another amazing Aha was when Reid Lyon invited me to go to the meeting of reading scientists at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development once he took a job there as chief of the Child Development and Behaviour Branch. He organized a convention. Most of the other people were already getting a lot of money for grants. They were top top level researchers. He invited me because we had worked together in Vermont, and he knew my work and knew my background, and he thought I could contribute something.

I got in that room and I looked around, and thought “Well, there’s Joseph Torgeson, and there’s Sally Shaywitz, and there’s Virginia Berninger, and there’s Pat Lindamood. What am I doing in this room?” But that led me, because of a lot of encouragement from Reid and from other colleagues including Jack Fletcher, to learn about research. Eventually I got involved in doing several NICHD projects. That was definitely a big moment in my life.

Aha—How come teachers aren’t being taught these things?

Laura Stewart:

So when you took that class with Carol Chomsky and you went on to study with Isabelle Liberman, looking back in your experience as a clinician, was that the moment that you said to yourself, “Oh, no wonder I felt ‘inadequate and ineffective’ because I just didn’t have this knowledge to drive my practice?”

Louisa Moats:

Absolutely. That’s when I started thinking, “Wait. If this is so meaningful to me and changes my ability to understand everything about what’s going on in the instructional situation, how come teachers aren’t being taught these things?”

It took me another decade from when I got out of school, and was in private practice in Vermont. I ended up being a sort of country doctor in a private practice there—over the space of 15 years, I evaluated 2,000 individuals, and that was a real education in the real world about people’s lives being affected by reading difficulties, from the poorest kids in the most rural setting to professors at Dartmouth College, down the road.

That was a fascinating experience. But the whole time I was doing that consulting with schools and teachers, it occurred to me that most of the people who were reading my reports didn’t understand what I was talking about, because the teachers didn’t have the advantage of the same education I had. So I started thinking that I need to do something about that. That’s when I started working up courses to teach what I thought teachers needed to know. That was a battle then, but you can see where it’s gone now.

Speech to print as groundbreaking

Laura Stewart:

I want to go back to Speech to Print, because Speech to Print was such a groundbreaking text. Why do you think that was, and why do you think it still is?

Louisa Moats:

Speech to Print came out of my need to have a text to teach with…I started the courses actually a decade before the book was printed. I formulated these courses and taught them at St. Michael’s in Vermont and taught them at the Greenwood Institute in Vermont. And I had these big notebooks. Anybody who has any colleagues who came to the Greenwood Institute, they might still have their huge notebook, mimeographed papers, and worksheets. I realized this wouldn’t do.

I think Brookes Publishing approached me and asked me to do something like this. While I was doing the NICHD research project in Washington, and also trying to teach the teachers there, I wrote the book. It came out in 2000. To answer your question about why it was groundbreaking, I think it’s because the content tries to teach as much about language that would be useful to someone who is a literacy instructor. I try to teach stuff that for me has been directly applicable to work teaching reading and writing, and oral language in the classroom, but mainly reading and writing.

I tried not to just go on about stuff like how interesting it is that other languages have different grammars, etc. I tried to minimize that kind of thing, partly because I’m not an expert in it. But I wanted everything in there to be a grounding for teachers who would study pretty hard. It’s not an easy text. I’m filling gaps because most teachers then and it’s still the case today that very few educator preparation programs have the course offerings that include the information, or if the information is there, it’s an ancillary thing—it’s “Go read it on your own.”

Laura Stewart:

If people are going into speech pathology, for example, but not necessarily for educators.

Louisa Moats:

Yes, it’s interesting, in the beginning the book got more attention from the SLP community. They have liked the book and asked me to speak at conferences years ago when I was doing that. But now, like in Idaho, the state based a whole project called Smart Project on the textbook. So that’s been really fun to see how that has played out, and the teachers say “Well it was rigorous. But I’m glad I learned these things.” And I taught the coaches and the coaches are teaching a lot of teachers. So it’s kind of fun because so many people say, “Oh, this is enlightening. This is information I needed. Why didn’t anybody teach me these things?” So that has been rewarding.

Still the missing foundation in teacher education

As I look at the text now, I think “Oh, things are changing, and I need to change it again.” I don’t know if I have it in me to do another edition, but I do think it’s because this is still the missing piece. That was the first article I wrote—about the missing piece—the missing foundation in teacher education. It is what I put into Speech to Print.

You asked me how long it took to clarify these ideas that are what you call my conviction. It incubated for years as a recurring thought—”Wait! This isn’t right. This is a really great teacher who doesn’t know these things that should be foundational knowledge. Can’t we do something about this?”

Empowering teachers with knowledge and clarity

Laura Stewart:

I think yours is a great lesson in following your curiosity. You managed to follow your line of inquiry, to try to figure this out and I think that’s really a helpful lesson for other people that are on a journey. I wish it were more accessible to them in their teacher preparation programs on a very widespread basis.

Louisa Moats:

It’s true. You could call it a kind of fixation, too. I have some colleagues who will totally change their focus every five years or so, and get into something different or research something different. I think I am a one-track pony about this issue because it hasn’t been resolved. And because day after day I see the evidence in interactions I have with teachers, things I see online, comments on the Facebook chat groups, questions teachers ask. And I think “Well, if you had had the background that you needed, you wouldn’t be asking this question, or you wouldn’t be confused about this. You would have clarity that would give you that sense of empowerment so that you’d become totally confident that you could lead your students into the kind of insights that will empower them and enable them to learn.”

Background on NICHD and Smart Project

Laura Stewart:

A couple of questions have come up in the chat. Could you just give everyone a quick refresher on the NICHD? Not everyone knows about that. And then please give us a little bit more about the SMART Project.

Louisa Moats:

NICHD stands for the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. It is one of the institutes under the National Institute of Health, which is that huge federally-funded organization in Bethesda, Maryland that does most of the grant-funded research in basic medical science. And you have to wonder, well, what are they doing mucking around in reading? When Reid Lyon became the director of the Reading Research program, several 100 million dollars were disseminated through the NICHD for reading research, both in basic processes like how kids process language, neurological research connected with educational research, and so on.

One of the things I do in my lectures when I have a chance is to show the map of what that research network involved all over the country. It was the best, most rigorous, most controlled, most well supervised program that has yielded the greatest volume of research about reading. And when we talk about the science of reading, what comes to my mind is all of these dots on the map, all of these centers and many of them collaborate with centers overseas. And it’s gone on from there.

The SMART Project (Striving to Meet Achievement in Reading Together), is sponsored by the Department of Education in Idaho. We’re in the third year now. Mary Dahlgren of 95 Percent Group’s Tools 4 Reading has been part of it as well, teaching about her Kid Lips program with phonics instruction for little kids based on the Sound Wall. So the SMART Project has been a grassroots me-to-the-coaches and coaches-to-the-teachers educational process using Speech to Print, and Mary Dahlgren’s materials along with other things that have been brought in. And they’ve gotten a very big effect size on growth in teacher knowledge through this process, which is wonderful, and the teachers who are practicing what they’re learning are getting much better results with their kids.

Laura Stewart:

That’s the great key, isn’t it, when you can make that connection between teacher knowledge to student outcomes? How long has that been going on, Louisa?

Louisa Moats:

This is the third year now. There are hundreds of teachers who are getting on board and learning a lot more, and doing a really good job with our kids.

LETRS and keys to success

Laura Stewart:

That leads me to talking about your leadership because you are considered one of the greatest and most influential literacy leaders. And you’re really a champion for teachers. We know when you wrote LETRS, that was really transformational for teachers’ lives. So has the breadth of that taken you by surprise at all? And, more importantly, what are the keys to success—what are the non-negotiables when it comes to a widespread professional learning initiative like that?

Louisa Moats:

The keys to success…first of all, there has to be real conviction behind what is being taught and it has to be very carefully worked over. It has to be responsive to criticism. That’s really important. I mean, anything that I write becomes dated after a few years. I wish I could revise everything much faster.

You know, as far as my leadership, it’s curious, because I have never been a school superintendent. I’ve never been a state director. I’ve never worked for the federal government in a policy position. I haven’t been an elected representative. I haven’t done any of those things. I’m grateful and humbled by your using that language for what I’ve done. I think of myself really as beating the same drum relentlessly in every forum that I’ve had an opportunity to do it, perhaps.

I think it’s being unafraid to act on your convictions and having a vision of what is possible and really important, and not giving up when the going gets rough if you know that what you are pursuing is right and valuable. I’ve always had to ask myself that question many, many times. Am I teaching people the right stuff? Is it going to lead to better practice? Is it necessary? Because some of my critics say, “Oh, that’s not necessary. You can get this job done much more quickly.”

Well, that’s not what I think is true, because I did a lot of studies of teacher knowledge, and in the course of the big study we did in Washington that went on for 5 years, where I was responsible for the outcomes, I could observe up close the learning process of all the teachers who were in the project, and it could not have been done in a quick and dirty way. It could not have been done with a few short sessions. It certainly could not have been done just by giving them a program and telling them to teach it.

And the fallacy still in policy-making land is that this is all about adopting a program, telling teachers they have to use it, and then sort of brow beating them. But we even have some studies—I cite them in various papers—that show that teachers who don’t have the requisite knowledge base cannot use a program effectively or will not use it effectively. The best combination is teachers who have the background knowledge and understanding of language and reading psychology, and then are given a really good tool to work with.

Laura Stewart:

Exactly. I always go back to this: If you have this knowledge base and then you’re given the wrong tool to try to actualize it in your classroom, that is a crisis for many of our teachers.

Louisa Moats:

It’s ongoing today. I get messages all the time from teachers saying, “I know what I’m supposed to be doing. My district has adopted this awful thing” while they don’t put it like that. They say, “What do you think about the XYZ?” I debate whether or not to tell them what I think. There are some really good ones out there.

Ready for part 2?

Click here to read now!

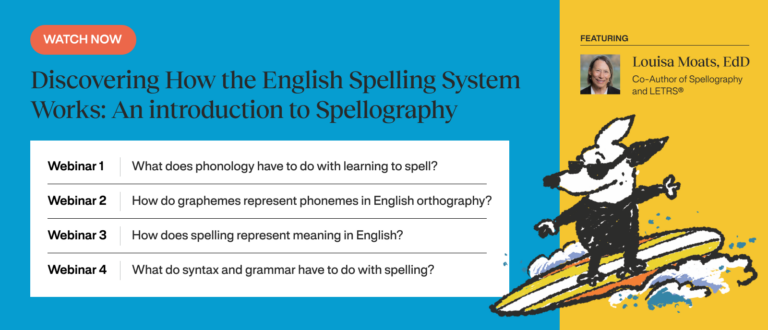

Learn more with Dr. Louisa Moats

In this four-part webinar series, “Discovering How the English Spelling System Works: An introduction to Spellography”, taught by Dr. Louisa Moats, co-author of Spellography, we will break down the layers of language and help educators see how the various parts work interchangeably together and build upon each other. Spellography is a classroom-tested program that explicitly teaches spelling concepts to help students make sense of the English spelling system and become better at understanding, reading, and writing words.

About 95 Percent Group

95 Percent Group is an education company whose mission is to build on science to empower teachers—supplying the knowledge, resources and support they need—to develop strong readers. Using an approach that is based in structured literacy, the company’s One95™ Literacy Ecosystem™ integrates professional learning and evidence-based literacy products into one cohesive system that supports consistent instructional routines across tiers and is proven and trusted to help students close skill gaps and read fluently. 95 Percent Group is also committed to advancing research, best practices, and thought leadership on the science of reading more broadly.

For additional information on 95 Percent Group, visit: https://www.95percentgroup.com.