14 phonemic awareness activities for students

Phonemic awareness is one of the most important early foundational skills that children need to learn to read. Research has shown that teaching phonemic awareness to young children significantly increases their later reading achievement. Mastery of phonemic awareness is one of the strongest predictors of later reading success which means it is equally important for ALL beginning readers to receive core instruction in phonemic awareness, right from the start.

Perhaps the most critical and least-practiced component of effective early instruction is phoneme awareness. Awareness of the sounds that make up spoken words, facility at manipulating those sounds, and the links between speech and print must be mastered for students to be fluent readers and accurate spellers of an alphabetic writing system like ours.

Dr. Louisa C. Moats

What is phonemic awareness?

Think of phonemes as the sound of speech that can be represented with letters. Phonemic awareness is the awareness of and ability to isolate and and manipulate the smallest sounds in spoken language—the phonemes. Phonemes, the smallest units of sound inside of words, are represented by graphemes. Graphemes, or written representation of phonemes, can be individual letters or groups of letters that represent single sounds. For example, sheep has three phonemes (/sh/-/ē/-/p/) represented by the graphemes sh-ee-p.

Why phonemic awareness matters

Phonemic awareness is a foundational reading skill that plays a vital role in a student’s journey to becoming a fluent, confident reader. Children can actually begin learning phonemic awareness skills as soon as they start recognizing words—through easy games and activities— long before they enter school.

Although there has been some difference in opinion about whether the larger units of sound (syllable awareness, rhyming, etc., sometimes referred to as phonological sensitivity) needs to be explicitly taught when children enter school, the most recent studies have been clear that it necessary to master phonological awareness in order to begin instruction on phonemic awareness. These skills can be used (as it is in 95 Pocket PA™), however, in the beginning of the year to help establish instructional routines and to learn vocabulary.

According to the International Dyslexia Association resource, Building Phoneme Awareness: Know What Matters, “Multiple findings also corroborate that programs are effective when they begin with a focus on phoneme awareness rather than phonological sensitivity, and highly so when instruction then links phonemes with graphemes. This is documented both for beginning readers and for students who have struggled with acquiring reading skills. This research indicates that phonological sensitivity instruction (with larger units such as rhyme, syllables, and onset-rime) is neither a prerequisite nor a causal factor in the development of phonemic awareness.”

Teaching students to identify and manipulate the sounds in words helps build a strong foundation for phonics instruction. Research in the science of reading over many years has shown that a child’s success with phonemic awareness is a powerful predictor of later reading success (Hulme & Snowling, 2009, p. 45).

Summary:

- Phonemic awareness instruction ensures that students perceive phonemes (speech sounds) accurately, which is a necessary foundation for learning letter-sound patterns.

- Since the “Report of the National Reading Panel” (2000) was published, research has continued to support the importance of teaching phonemic awareness in addition to phonics.

- Developing phonemic awareness is critical for success in reading and spelling because it supports understanding of the alphabetic principle.

- Many children who will struggle with learning to read have underdeveloped phonemic awareness.

How can teachers and parents help children strengthen phonemic awareness?

Mastering phonemic awareness involves a developmental progression for young children. For example, research shows that identifying beginning and ending phonemes is easier than identifying medial phonemes which are the phonemes in the middle of the word. The National Reading Panel research review emphasizes the need for explicit, sequential, systematic, and comprehensive phonemic awareness instruction.

To teach students about phonemes, students need to first understand the idea that all words are made up of sounds. This awareness can initially be taught through word play, using rhyming words to show that words have different parts.

Once students have an understanding that words are made up of small units of sound, they can practice phoneme isolation beginning with identifying the initial or beginning sound: the /k/ in “cat.”

When children are confident with identifying the initial sound in words and can perform activities to demonstrate this (such as grouping together objects that all being with the same sound) they can being identifying final sounds in words (the /t/ sound in “cat”) and the medial sound in words (the /ǎ/ sound in “cat”—typically the medial sound is the most difficult for children to isolate).

These skills can be taught through numerous activities, including word play.

Here we will detail activities that support students with all phonemic awareness skills including: phoneme blending, segmentation, and manipulation.

- Phoneme blending is when you can merge individual phonemes together to make a word whole. An example is blending /b/ /e/ /d/ together to create the word “bed.” Phoneme blending is particularly important for decoding (sounding out) words.

- Phoneme segmentation is the ability to break apart a word into its individual phonemes. An example is breaking down the word “red” into three phonemes /r/ /e/ /d/. Segmentation is particularly important for encoding or writing words.

- Phoneme manipulation is the ability to replace or take out phonemes in word to turn it into another word. This can be done by changing the first, final, or medial phoneme. An example: cat → mat which is done by changing the first phoneme from /k/ to /m/. While manipulation isn’t considered a necessary skill for mastering phoneme awareness, it is helpful for children in learning how to read, write and spell.

Should teachers introduce graphemes during phonemic awareness instruction?

Although the belief used to be that we should not introduce letters during phonemic awareness instruction, research has since shown us otherwise.

We now know that when designing phonemic awareness instruction, it’s valuable to build on what students already know about speech and quickly introduce graphemes to help anchor this knowledge. As Dr. Louisa C. Moats explains, “The more students know about a word being used for phonemic awareness instruction, the easier it will be for them to learn, recall, and apply the word knowledge.”

She recommends extending oral activities by having students identify and write the grapheme that represents the initial sound, which strengthens the crucial sound-symbol connection and activates orthographic processing. Moats emphasizes that engaging all four processors (phonological, orthographic, meaning, and context) leads to deeper learning experiences that students are more likely to retain (Moats, 2024).

14 Phonemic awareness activities

Phonemic awareness activities are an engaging way to teach children this core literacy skill. Here are 15 fun and engaging activities for young children, as well as several activities for older students that can be adapted for home or school.

Instructional Tips

Before you begin, read over these first few helpful teaching tips from 50 Nifty Activities for 5 Components and 3 Instructional Tiers. They will help guide your instruction.

- Base your instructional choices on assessment results. Continue to monitor students’

progress in order to judge the efficacy of your instruction. - Plan an I Do, We Do, You Do format, where appropriate. Modeling, guiding practice with feedback, and then releasing the students for independent practice will set the stage for successful learning. Remember that practice does not make perfect; only perfect practice (guided with feedback when necessary) makes perfect.

- Create opportunities for frequent, distributed practice. Frequent, distributed practice is more effective for retention and recall of information than longer, less frequent learning sessions.

(For more instructional tips from 50 Nifty Activities, grab your copy here!)

1. Sound formation awareness

An easy multisensory game is mirror mimicking. Using mirrors, have students pronounce different words. While they speak, have them watch their faces to see what shapes their mouths are making as they make certain sounds. This will help students connect the sound they’re making to the words they’re seeing on a page.

You can use anything from a big mirror on the way to small handheld mirrors to help with teaching this activity.

2. Onset-rime—guessing game

Students work in pairs using picture cards and onset and rime clues to guess words. Students alternate drawing picture cards. The student who draws the card gives the clues one at a time (e.g., “It starts with /b/ and rhymes with cat”) until the student guesses a word (e.g., “bat”). Then they reverse roles.

3. Initial phoneme identification—treasure box

In this interactive activity, students will get to go on a treasure hunt to work on initial phoneme identification. The teacher (or parent or caregiver) will tell students to search for things starting with a matching sound. For example, if the phoneme is /b/ students will need to search for something that starts with /b/ and add it to the treasure box.

In the end, they’ll go through what is in the treasure box to determine if it matches the correct sound. This activity can be done both inside and outside.

4. Phoneme isolating—Sound Quest game

Students sort pictures according to initial, medial, and final sounds. Using double-picture cards, students individually determine if the two pictures share the same initial, medial, or final sound. FCRR offers downloadable instructions and picture cards for the sound quest game.

5. Phoneme blending—blending i-Spy

This is a very common game that you can adapt in a number of ways for different ages. A teacher or parent/caregiver begins by modeling, “I spy a /h/ /a/ /t/. What do I spy? Yes, it is a hat!”

Adjust the level of difficulty as the student’s blending skills develop.

At home, this game could be played in the kitchen (I spy a /c/ /u/ /p/) or on a walk (I spy a /d/ /o/ /g/, I spy a /c/ /a/ /t/).

6. Blending—blend baseball

You can even use baseball to help with phoneme blending. In this activity, you’ll split your class up so there are two teams. From there, a student is chosen to be “up at bat.” When at bat, you (or whoever you deem to be the pitcher) will give them a word by providing only the phonemes. So, you will say /p/ /e/ /t/. If the child correctly says the word “pet” they’ll then get to move to first base and the next child on their team gets a word to blend. This could be changed to segmenting baseball as well!

7. Blending—shout it out song

Changing familiar tunes is both a fun and easy way to work on phonemes with children. You can change the words to songs such as “If You’re Happy and You Know It, Clap Your Hands.” Instead of singing the regular words for the song, education Professor Hallie Kay Yopp recommends tweaking the words to sing:

“If you think you know this word, shout it out!

If you think you know this word, shout it out!

If you think you know this word,

Then tell me what you’ve heard,

If you think you know this word, shout it out!”

After students finish singing those phrases, then the teacher, parent, or caregiver will speak the individual sounds of the word such as /p/ /o/ /p/. It will be up to the children to blend those letters together and yell out the blended word “pop.”

8. Phoneme isolating and segmenting—old Macdonald had a farm song

Another popular tune ideal for working on phoneme isolating and segmenting is the classic song, “Old MacDonald had a Farm.” For this song, you start by encouraging children to isolate the first sound in a word by tweaking the words to sing:

“What’s the sound that starts these words:

Dog, dad, and den?”

After you sing the first part, wait for the students to answer before heading into the second part of the song:

“/d/ is the sound that starts these words

Dog, dad, and den.

With a /d/, /d/ here, and a /d/, /d/ there,

Here a /d/, there a /d/, everywhere a /d/, /d/.

/d/ is the sound that starts these words:

Dog, dad, and den”

Work with the children to identify the beginning sounds in words until they feel comfortable. After that, you can make the activity more difficult by focusing on the middle and end sounds of words. For middle sound identification, you can sing:

“What’s the sound in the middle of these words:

Treat and leap and seat?

/ee/ is the sound in the middle of these words:

Treat and leap and seat.

With an /ee/, /ee/ here, and an /ee/, /ee/ there”

Finally, for ending sound identification, you can sing:

“What’s the sound at the end of these words:

Lake and luck and seek?

/k/ is the sound at the end of these words:

Lake and luck and seek.

With a /k/, /k/, here and a /k/, /k/ there…”

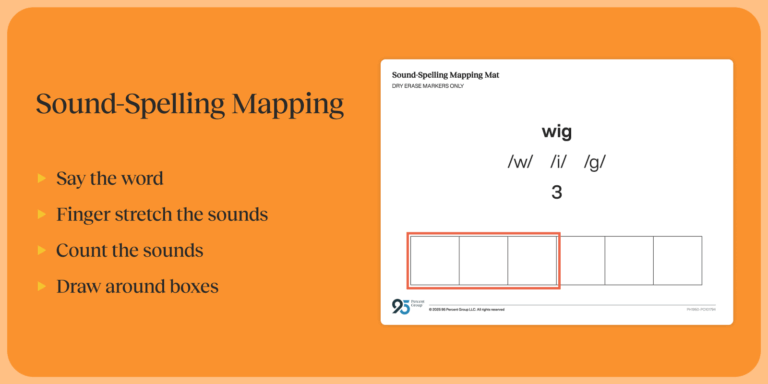

9. Segmenting phonemes—Sound-spelling mapping for 2, 3, 4, 5 phonemes

Sound-Spelling Mapping is a tool that helps children segment words into phonemes. It’s similar to Elkonin Boxes, pioneered by D.B. Elkonin, a Russian psychologist. Students count sounds in each word first and move a chip into each box to represent each sound. For example, ask the student to put a chip for each letter in the word “take.” This activity will help them visually break down the sounds of the word to /t/ /ā/ /k/.

10. Sound Toss Game

Sound Toss develops phonemic segmentation and blending skills by having students listen for and manipulate sounds in words.

- Begin by having students stand in a circle and play a brief round of Silent Ball to establish a quiet listening environment.

- For the main activity, students toss a Koosh ball or similar soft object to each other while performing sound-based tasks appropriate to their skill level (following your curriculum’s scope and sequence).

- The receiver of the ball must respond with a word that meets the criteria set for that round (such as rhyming words, words that begin with a specific sound, or segmenting/blending exercises).

- For added engagement, time the activity to see how many correct responses students can generate in one minute.

- Small groups can compete against each other or try to beat their previous scores. Allow both real and make-believe words, but ask students to identify when they’re using imaginary ones.

(Adapted from 50 Nifty Activities for 5 Components and 3 Tiers of Reading Instruction by Judith Dodson)

11.Walkabout Sound Matching

This movement-based exercise strengthens students’ ability to recognize and match beginning sounds – a foundational skill for reading development.

In this phonemic awareness activity, distribute one picture card to each student and model how to identify initial sounds by holding up a picture like “pot” and saying /p/. Have students take turns standing, showing their picture, and stating its initial sound. Then select one student to walk around displaying their picture until they find a classmate whose picture begins with the same sound (like “pie” next to “pin”), at which point they stand together.

After demonstrating with 2-3 examples, have all students circulate simultaneously to find matching initial sounds. For added practice, collect and redistribute cards to repeat the activity.

(Adapted from 50 Nifty Activities for 5 Components and 3 Tiers of Reading Instruction by Judith Dodson)

12. Blending, Segmenting and phoneme manipulation

Challenge students with quick phonemic awareness activities that can be done during transitions or spare moments.

In Word Construction, say individual sounds in sequence (e.g., “/g/ /r/ /ā/ /p/”) and have students blend them to identify the word “grape.”

For Word Deconstruction, say a complete word like “late” and ask students to segment it into its component sounds (“/l/ /ā/ /t/”).

Extend these activities with phoneme manipulation by having students create new words through addition, deletion, or substitution of sounds—for example, “If we start with ‘late’ and remove the /l/, what’s our new word?” or “If we change the /r/ in ‘ran’ to /p/, what word do we make?” These games help students understand how changing just one sound creates entirely new words, a concept that often fascinates young learners.

13. Phoneme-grapheme connection—sound walls

Many educators are transitioning from “word walls” to “sound walls”. Word walls are organized alphabetically, from A to Z and focus on letters. Sound walls are organized around the sounds in speech, and focus on phonemes and articulation. Along with showing phonemes, these walls also show kids lips cards so children can see how the sound should be pronounced.

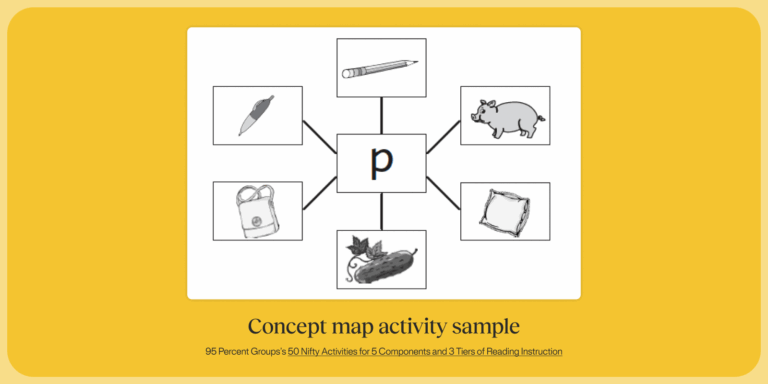

14. Concept maps for sound association

Create a visual concept map on the floor using card stock to help students connect words with common sounds. This activity builds phonological awareness and word consciousness through active participation.

Key Steps:

- Establish the purpose: Students will practice identifying sounds in words to improve reading, writing, and spelling.

- Introduce a target sound (beginning, middle, or ending).

- Place the target letter card (e.g., “p”) in the center of the floor concept map.

- Arrange pictures beginning with the target sound (e.g., pen, pig, purse) in sections around the map.

- Give each student a picture card.

- Have students determine if their picture contains the target sound and, if so, stand in the appropriate section of the concept map.

This activity reinforces sound-symbol relationships through physical movement while promoting comparison and contrast of similar sounds in words.

Adapted from: 95 Percent Groups’s 50 Nifty Activities for 5 Components and 3 Tiers of Reading Instruction

Tips for making phonemic awareness activities fun

When putting phonemic awareness activities into action use a multisensory approach to make it fun and interactive for all ages of students. For example, you can use games, songs, movement, storytelling, soft toys* and role-play.

Research shows that phonemic awareness activities for students should be kept short and engaging (5-10 minutes).

*Note: Many educators recommend using soft toys instead of puppets so that children can watch the adult’s face and mouth articulate the sounds directly.

95 Phonemic Awareness Suite™—research-based phonemic awareness instruction

Our 95 Phonemic Awareness Suite™ is a new, comprehensive phonemic awareness solution that includes Tier 1 instruction, assessment, differentiated Tier 2 instruction, and professional learning—all aligned to provide a consistent instructional dialogue for teachers and students. Aligned with the latest research on phonemic awareness, it’s everything needed to build critical foundational skills and set students up for reading success!

95 Phonemic Awareness Suite components include:

- Tier 1: 95 Pocket Phonemic Awareness™, 50 weeks of lessons, each 10 minutes per day (K-1)

- Assessment: 95 Phonemic Awareness Screener for Intervention™

- Tier 2: 95 Phonemic Awareness Intervention Resource™, lessons cover alphabetic & phonemic awareness, with Kid Lips instruction built-in

- Professional learning for teachers and reading specialists

Learn more

Are you interested in learning about how you can bring an effective and efficient structured literacy approach, grounded in the science of reading, to your school or district? Contact us today.

Sources

- 50 Nifty Activities for 5 Components and 3 Tiers of Reading Instruction by Judith Dodson

- Ashby, J., Martin, M., McBride, M., Naftel, S., O’Brien, E., Paulson, L. H., & Moats, L. C. (2024). Teaching Phoneme Awareness in 2024: A Guide for Educators. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1tPwupou7EqctDO50XtfvMGxfJAx7xPk9?usp=share_link

- Cunningham, 1989; Foorman, Francis, Fletcher, Schatschneider, & Mehta, 1998; Lundberg, Frost, & Peterson, 1988

- International Dyslexia Association, Building Phoneme Awareness: Know What Matters

- Inverizzie, 2003

- Goswami, 1994, p. 36

- Florida Center for Reading Research (FCRR)—from the “At Home” series for families

- Hulme, C., & Snowling, M. J. (2009). Developmental disorders of language learning and cognition. Wiley-